Recess Shrinks At Seattle Schools; Poor Schools Fare Worst

In decades past, elementary students had recess several times a day.

Today, parents and teachers across the country report dramatic cutbacks to that free time. In Seattle, the length of recess varies dramatically from school to school – from an hour to just 15 minutes.

A KUOW investigation has found that the average time Seattle students are getting for recess has steadily declined over the past few years. The investigation also revealed that schools with the shortest recess times have more low-income students and students of color.

Many principals – especially those at schools with a higher percentage of low-income students – said they limit recess to avoid discipline problems.

That has played out at West Seattle Elementary School, where there is no school recess schedule. Instead, teachers decide when to take their students out to play. At most Seattle schools, building-wide schedules determine when kids go out for recess.

West Seattle Elementary Principal Vicki Sacco said she made that change when she became principal four years ago. When she took over, the elementary school had been identified as a failing school.

“When I started to investigate where some of the problems were arising, I did some research and recognized that a lot of the issues with behavior, starting there, happened at recess," Sacco said.

Sacco said too many fights started on the playground. So instead of having big, grade-level recesses monitored by instructional assistants, Sacco told her teachers from now on, they would take their own students out.

She also warned them not to let kids play too long – no more than 15 or 20 minutes at a time. "Really any longer than that, you start to have behavior problems," Sacco said.

"Kids get involved in a game, somebody hits somebody too hard with a ball, they get angry,” Sacco said. “So it really minimizes the behaviors, kids seem happier, and I just think it’s better for the instructional day."

She said that because teachers decide recess, she can only estimate how much time students spend outside. "I would say the average for our third- through fifth-graders is probably about 15 to 20 minutes a day, and our kindergarteners and even first-graders often might go out twice, but just for shorter blocks of time," she said.

That puts West Seattle toward the bottom of the list citywide for the amount of recess young students receive.

Many schools offer even less.

Recess Dwindles

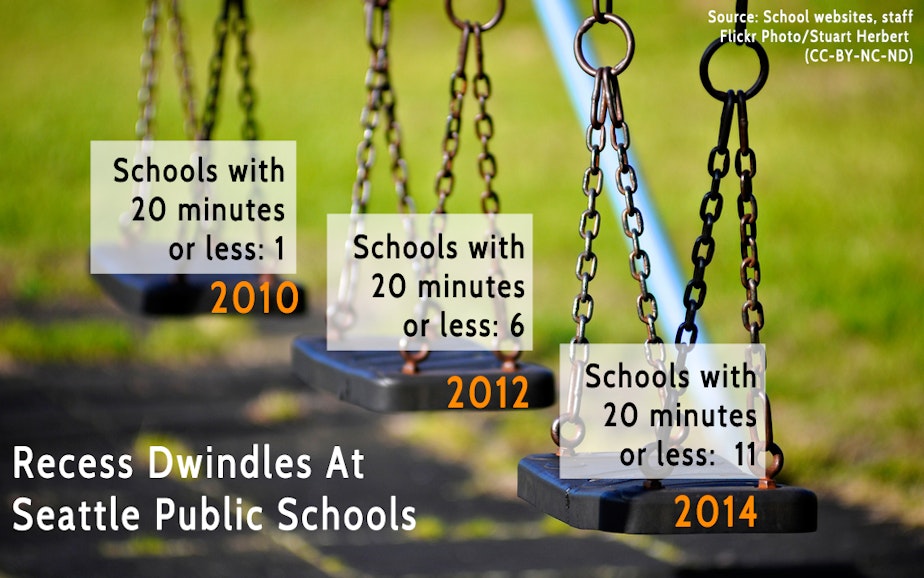

When KUOW started tracking recess times four years ago, we found only one Seattle school that reported average recess times of 20 minutes a day or less. Today, 11 schools offer that little recess.

What hasn’t changed since 2010 is that schools with less recess have more low-income students and students of color.

"Actually, I haven’t been aware of the trend in data, but I could realize that it’s true," said Lori Dunn, the physical education program manager for Seattle Public Schools.

Dunn said issues of equity are longstanding in the district – like determining how much recess students receive. "It’s not okay to go to one end of our system and see not the same thing being offered at the other end of our system," she said.

Dunn said the district is working to improve equity issues, and that she expects schools will equalize recess time as school leaders become better-informed about the benefits of playtime.

But she said there are no plans in Seattle to require that schools provide a minimum amount of recess.

Fuzzy Data

There are no state or federal laws protecting recess time, either. Nor is there clear data on how much time students get for recess across the state or the U.S.

But Group Health pediatrician and childhood obesity researcher Paula Lozano said there is a known nationwide disparity in the amount of recess and PE disadvantaged students receive.

"Those students are the ones we also know have higher rates of obesity, and for whom academic achievement in school is even more important. So we’re doing this backwards," Lozano said.

Lozano said low-income students are less likely to have opportunities for exercise after school, like organized sports or a backyard.

"I also think a lot about the social skills that come with recess," Lozano said.

"I asked my older daughter today, who’s now in college, what she remembers about recess, and she said, 'It’s where I learned to stand up for myself,'” Lozano said. “Playing imaginary games in the treehouse, or under the jungle gym, a lot of negotiation goes on there in the elementary-aged kids.”

Even if that negotiation often goes awry, and fights break out, Lozano said that’s still no reason to cut back on recess.

"If that was happening in math class, would we stop math class? I don’t think so," Lozano said.

"If there are problems with kids fighting at recess, that’s where I want to go. I want to go there, and say, 'Why are these kids fighting? Why is this a repeated problem? Which kid is it? What do they need? What are they frustrated about? Let’s deal with that.'"

Back at West Seattle Elementary, kindergarten teacher Amanda Poch said her students often get about 30 minutes of recess a day, compared to twice that amount at the school where she started teaching.

Poch views recess as not just free time but an important learning tool.

"The research I’ve read lately says that if there’s something that you want kids to be able to concentrate on a lot or really focus in on, take them out to recess before you get to it, then they’ll be more ready," Poch said. "I’m trying to employ that a bit more. I’m having good results from that in my classroom."

Poch is concerned that recess cutbacks – to prevent fights – are taking away the main part of the day where her kindergarteners learn how to resolve conflict.

"How are they going to be able to deal with that as adults? I mean, what adult doesn’t have conflict in their day? And I worry about that with this generation of students," Poch said.

Poch said kids crave the time.

"That’s the biggest reward in the world to them. I could offer them candy or going outside, and they’d want to go outside every time."

The three-part radio series No Time For Play examines how schools in the Seattle area are increasingly limiting kids’ physical activity and play times. It was reported by Ann Dornfeld and edited by Carol Smith.

Seattle-Area Kids Don’t Get Enough P.E., But Who Is Keeping Track?