Parasites have a bad rap but play an important role in the animal kingdom

New research points to a steep decline of parasites in Puget Sound fish. Climate change is the likely culprit.

Tapeworms, lice, nematodes — no one wants another organism using them as a home, but parasites do play an important role in ecosystems.

"The early indications are that parasites serve a lot of the same functions as predators do, including keeping a cap on the abundance of species that otherwise would grow out of control," said Dr. Chelsea Wood, an associate professor at the University of Washington School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences.

Not only do parasites potentially control their host population, they also help energy transfer up the food chain. Parasites can make prey host weak, slow, and clumsy and, therefore, easier for a predator, and potential new host, to catch.

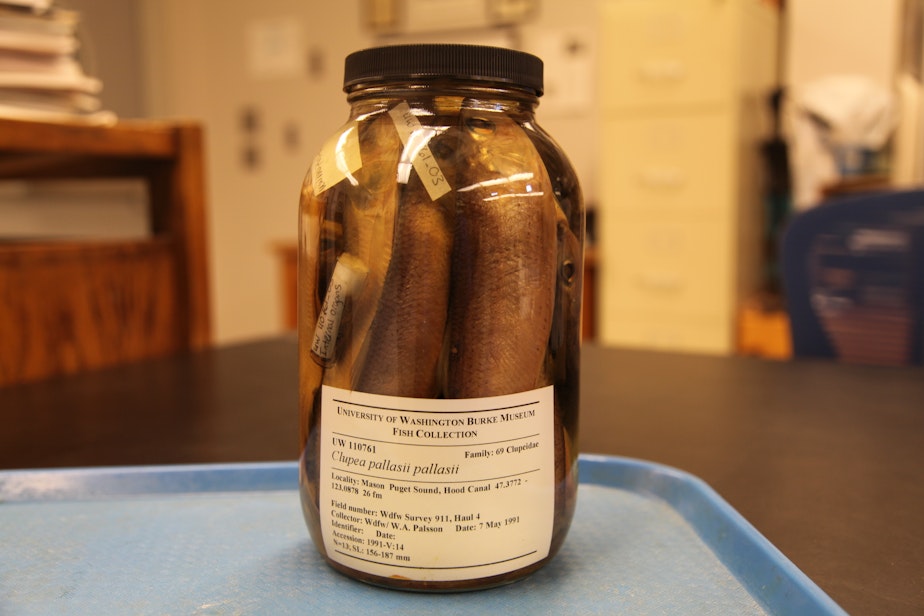

Wood was the lead author of a study appearing in the science journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, which found a steep decline in aquatic parasites in Puget Sound fish over the last 140 years.

Wood expected there to be parasitic winners and losers as time progressed from the 19th century to today. However, she found that there was a tremendous amount of decline, specifically in parasites with complex life cycles, or parasites that require multiple hosts throughout their lives. Those parasites declined about 11% per decade.

Sponsored

In the study, researchers looked at 12 different pollutants as potential causes of the parasite decline, along with fish stock numbers to test whether the abundance of fish controls the abundance of parasites.

"Neither one of those factors could explain the change over time. It was climate that was closely tied to the decline of the parasites," Wood said.

The field of parasite ecology is relatively young and researchers like Wood have an uphill battle in getting people to care about parasites.

"If it were happening in a group of animals that people actually cared about, like mammals, or birds, or even insects, there'd be a lot of conservation attention," Wood said.