Looking back at Seattle's CHOP, one year later

It’s been one year since people protesting police violence marched to Seattle's East Police Precinct and found that police had abandoned the area. That started a protest zone that garnered national attention — the CHOP.

After a Minneapolis police officer murdered George Floyd on May 25, 2020, anti-police brutality demonstrations sprung up around Seattle. People marched from downtown up to the East Police Precinct building on Capitol Hill. The precinct became the epicenter of protests.

Angelica Campbell said it was important to keep showing up to the East Precinct day after day.

"I'm going to have children that are Black," Campbell said. "And I don't want to come out here and march because they got shot.”

From May 30 through early June, Campbell and thousands of others pressed up against a wall of heavily-armed police outside the precinct. Every moment felt tense. Clashes and arrests often broke out.

Sponsored

One night, June 2, a protester threw a frozen water bottle over the police line. Seattle police responded with eight flash bang grenades in under 30 seconds. The explosions lit up clouds of tear gas hanging in the air.

Flash bangs and more tear gas continued for the first week of June. On the morning of June 8 protesters showed up to the precinct prepared for another day of squaring off with police.

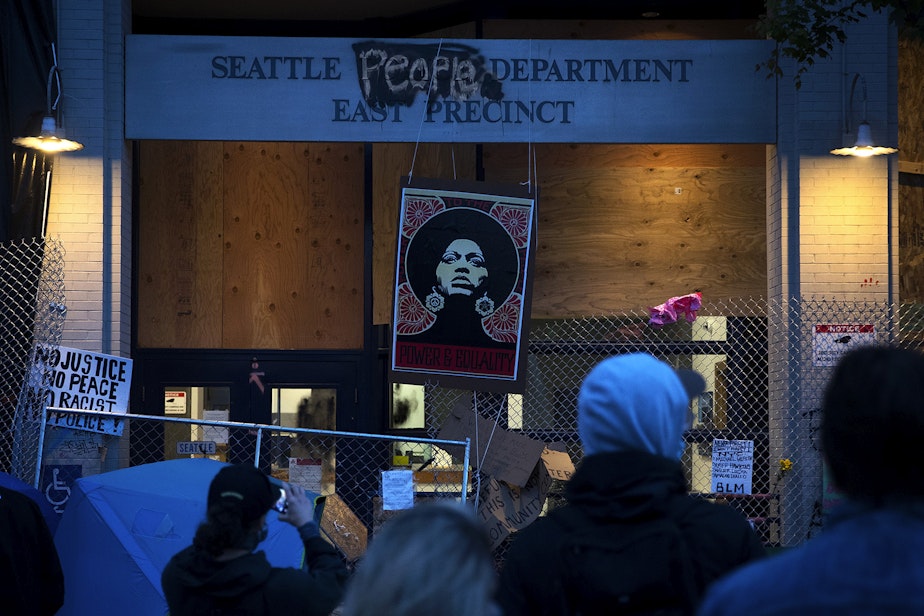

But on that morning, to everyone’s surprise, the police weren’t there to meet them. The East Precinct building had been boarded up. The hundreds of police officers and state patrol in riot gear, the armored trucks, the pepper spray and rubber bullets, seemed to have all disappeared. Nobody knew why the police had left or where they had gone.

Activists, who had been calling for the abolishment of police, saw this as a victory. That Monday protesters set up their own makeshift barriers to close the roads surrounding the precinct and set up camp around the area. At first protesters called the area the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone (CHAZ), but that changed to the Capitol Hill Organized Protest, or The CHOP.

Sponsored

People were covering the intersection of 11th Avenue and Pine Street with street art. Free food stands, like the No Cop Co-Op, lined the sidewalks. And a lot more people started showing up to see the new space. Tiffany Young was there for the first day of the CHOP with her friend.

"All I've seen is kindness. People are giving people water, making sure people are OK. It's really peaceful and it's just a beautiful thing. If anything, I've been very inspired," Young said.

By the night of June 8, hundreds of activists were camping in and around Cal Anderson Park. There was a conversation corner full of old couches for people to discuss the future of the Black Lives Matter movement. Someone set up a projector and people sat around, right in the middle of the now closed street, to watch movies about systemic racism. The Marshall Law Band set up a stage and became the CHOP house band, playing almost every night.

Sponsored

For those first few days, the CHOP felt pretty peaceful. Silberio Ellis was one of the thousands who hung out at night, enjoying the absence of police.

“I’d rather be eating the pizza," Ellis said with a giant slice of cheese pizza in his hand, "watching movies and watching people paint and watching the art, you know what I mean?”

Not everyone liked those late night hang outs, however. Joe Pascual and his partner lived right next to the East Precinct.

"Yeah, we would definitely like things to go back to normal," Pascual said standing outside his apartment at the time.

Sponsored

They were on the ground floor and their front door faced the alley to the precinct. At night they’d take turns guarding outside as lots of people went down the alley to throw bottles at the precinct. There were also some barrel fires around the camp.

Just a few days before, Pascual had tear gas inside his living room. He didn’t expect he’d call the police back to his apartment.

"We've called actually tonight," Pascual at the time, "saying like, 'hey, do you guys have any idea when you're gonna be back?'”

By the second week of the CHOP, divisions among the campers were starting to show. Many Black Lives Matter activists felt the party vibe distracted from the original message about systemic racism in policing. Christeen Gounder said people should go home at night, and come back during the day to focus on protesting, not partying.

“People are not coming here for education," Gounder said. "People are not trying to learn something new today. Free food is what they're coming here for. Period. This is not a block party, we're not here for fun.”

Sponsored

People in the CHOP were also worried about how the police might show back up. At night, some protesters stood as lookouts at the entrances of the CHOP in case the police arrived. There were armed guards, too. It wasn’t always clear how the Seattle police were communicating with CHOP organizers, if at all.

“One of our real challenges there is trying to determine who is a leader or an influencer," said former Seattle Police Chief Carmen Best. "And that seems to change daily.”

It was during one of those late night parties on June 20 when everything at the CHOP changed. That night two people were shot right on the edge of the protest zone. One teenager was killed. Over the next week there were two more shootings in and just outside of the CHOP. After the third shooting a lot of campers left.

RELATED: 1 teen dead, another wounded in the CHOP

Just after 5 a.m. on on July 1, Mayor Jenny Durkan ordered Cal Anderson Park to be closed and the CHOP cleared.

Seattle Police arrived with parks crews early that morning. They closed the area to the public, hauled away tents in dump trucks, and took down the art surrounding the precinct.

All that was left was a large street mural going down Pine Street that read, "BLACK LIVES MATTER."