ICE detained immigrant children in Washington state. New documents pierce its secrecy

This story was published in partnership with Reveal.

A

rne Mortensen’s phone wouldn’t stop ringing that Tuesday.

It was July 7, 2020, in the middle of the second wave of the coronavirus pandemic and a month into the summer protests for racial justice. Mortensen – an oceanographer by training turned public servant – was one of three commissioners overseeing Cowlitz County, Washington, across state lines from Oregon and about an hour north of the Portland metro area.

“I’ve been bombarded by out of county calls on wanting to dissolve the ICE contract and wanting to release three detainees,” he typed out in an email to Chadwick Connors, the Superior Court administrator who ran the county’s youth detention program.

“Would you mind giving me the argument bullet points on this issue?”

For 20 years, the Cowlitz County Youth Services Center had been one of a handful of facilities that contracted with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement to hold a small number of immigrant youth who were living in the U.S. without legal permission and who ICE had determined pose a significant threat to public safety.

The program had always been shrouded in secrecy and faced questions about its legality. It had long been unclear how ICE decided to keep immigrant children there, how long the children stayed there and why they weren’t released to their families pending the resolution of their immigration cases.

Sponsored

But now pressure was building for answers in Cowlitz County, a timber community in the Pacific Northwest that leaned red in the last two presidential elections. The callers Mortensen encountered were worried this was another form of family separation, as lawyers for the children say most of them have family in the U.S. who could care for them. What’s more, advocates saw the immigrant children being treated differently from other children in the detention center, who were sentenced there on criminal charges.

Although U.S. citizen children were guaranteed legal representation, the immigrant youth were not. Months earlier, the center released all but four residents from detention to protect them against the spread of the coronavirus. Three of those left behind were immigrant youth. The county court said it couldn’t let those kids go – that was up to ICE.

Mortensen wanted to know more about the detained youth: Who were they? Connors, the court official, provided four lines in return. The detained immigrant children were all 17. One kid had been there about two weeks, one for more than a year.

“Sorry I can’t provide more,” the administrator wrote back.

Mortensen was livid. “Certainly you could tell me what the particular reason is for the stays,” he wrote. “How can I tell anybody that I have reviewed the matter. What will it sound like if I have to tell reporters or the like that I have no idea what is going on there, other than the same press release they and I read?

“I am not happy being so blind.”

ICE typically isn’t the federal agency in charge of detaining migrant children. That’s the Office of Refugee Resettlement, which is tasked with providing shelter for immigrant children who come to the United States without their parents or are separated from them.

However, using a loophole in the Flores Settlement Agreement, which decades ago created guidelines meant to protect immigrant children in federal custody, ICE officials can hold a youth who they deem to be “charged with, is chargeable, or has been convicted of a crime.”

That means the agency can detain migrant children even if they’ve never been found guilty in a criminal court or after they’ve already served their time. There’s no judicial or public process for how ICE makes these determinations; it is up to the agency’s sole discretion. And once children enter a facility like Cowlitz, they face another challenge: time. ICE can hold youth at these facilities until they turn 18. Then they’ll be transferred to adult detention centers, where they often face deportation.

Sponsored

For these reasons, the questions Mortensen was asking had long swirled around Cowlitz.

New documents provided exclusively to KUOW and Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting provide the most robust look yet at why and how children end up in one of ICE’s rare youth detention facilities.

Through a federal Freedom of Information Act lawsuit, professor Angelina Godoy at the University of Washington obtained hundreds of internal documents from ICE containing the details of 15 migrant youth who passed through the Cowlitz facility between 2015 and 2018. We’ve additionally spoken to three other teenagers to learn how and why they landed in places like Cowlitz.

In some cases, the documents show minors were accused of serious crimes like assault or robbery. But in records released for three of the youth, ICE did not list a reason for their detention.

Additionally, in 2019, a teen was arrested by ICE while agents were looking for another youth. He was never charged with a crime, though, according to court records.

In at least four cases, the children already had served their time in the criminal justice system or had been placed on parole and were free to go home, only to be picked up by ICE officials and detained once more. They effectively exited the criminal justice system only to be pulled back into an immigration void, with little explanation and without knowing what to expect.

The lawyer for one 16-year-old remembers waiting with the boy’s mother for him to be released after serving time in the juvenile justice system for a misdemeanor. They were expecting to bring him home that day in October 2019. But a sheriff at the juvenile detention center came out to let them know ICE had detained him.

In November 2017, a 17-year-old in Boston was accused of carrying a stun gun to school. The boy told officers that he kept the weapon for protection against “rival gang members,” according to a police report.

A few days after his arrest, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services terminated his Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals status, which had shielded him from deportation. ICE detained him for over 100 days. Records state he had a “verified gang affiliation,” a tactic often used by immigration officials that has come under scrutiny in the past.

Sponsored

After receiving a letter of support for his good behavior, that teen was released on a bail bond pending his immigration proceedings. ICE’s internal documents show at least five kids were sent back to Honduras, Mexico, Brazil and Finland.

In one case, one teen was held for 450 days. Samantha Ratcliffe, an immigration attorney at the Metropolitan Public Defender in Portland, Oregon, says she often wasn’t told why her clients were being held at Cowlitz. “It feels like this dark hole of secrets,” she said.

In a court affidavit, Ratcliffe said youth do not have access to the outdoors, only to a gym for exercise indoors – and that was prior to the pandemic. Afterward, youth reported they no longer had contact with clergy or support groups or had access to private mental health sessions with a counselor.

In a separate declaration submitted to county commissioners, Ratcliffe pointed out that “unlike the juvenile detainees in the criminal system, ICE, not the immigration judge, has considerable discretion on whether or not to detain youth, and where.”

Last year, the University of Washington Center for Human Rights published a damning report on the activity at Cowlitz, questioning its basic legality.

“Our research suggests … that in facilitating family separation and the indefinite detention of children without access to due process protections these facilities and ICE violate international human rights standards, the U.S. Constitution, and Washington and Oregon state law.”

Cowlitz County officials did not see it that way.

In their narrative, collaborating with ICE was a public service. Internal communications among Cowlitz commissioners show they were confident and in some ways proud of the contract.

“We have the capacity to provide this service in a humane and safe manner,” says one email from Commissioner Dennis Weber.

“And it does help underwrite the costs of operating this 24/7 facility, most of which goes to personnel.” Indeed, the county received $170 per youth per day. But for all the conversation buzzing around the county for its long-running contract, there was one voice that was glaringly absent: that of one of the child detainees in Cowlitz.

When 17-year-old Kaio Bispo and his girlfriend broke up in March 2020, he was devastated. He’d moved to the United States five years earlier from Brazil, coming on a travel visa with his younger sister to be reunited with his mother. They’d been raised by their grandmother in a small town as their mom sent back money from her housecleaning work in Georgia.

One day, right after the breakup, he was in a group text with several friends from his high school. One friend, Aoliabe Jacques, said he would pursue Bispo’s ex-girlfriend. Bispo was furious. So he sent a message back.

“I told him I was gonna kill him. And I posted a picture with a gun,” he said.

School officials noticed Jacques had been missing classes, so they asked him to come into the office. He told officials about Bispo’s threat but said he tried to convince the principal that his friend was just being hot-headed. School officials had already alerted the campus police. School officials also heard from the parents of Bispo’s ex-girlfriend, whom we’re not naming for privacy reasons.

In an email, her father called it a “very bad relationship” and expressed concern for his daughter’s life and safety.

“We have suffered a lot from this,” the father wrote. “Our daughter does not eat properly, she is afraid to stay home alone.”

The police reports say that during an argument, Bispo once grabbed the collar of her hoodie and yelled at her.

“Next thing you know, the police is at my house, and then I got arrested,” Bispo said. “That was the last time I see my mom.”

Bispo told police that the gun in the photo was a BB gun. And when police searched his home, they found an empty box for a BB gun meant to look like a pistol.

Cobb County prosecutors ultimately charged the teen as an adult with two counts: terroristic threats for threatening to kill another student and simple battery for making “physical contact of an insulting and provoking nature” against his former girlfriend, records state.

Bispo denies that he ever harmed his ex-girlfriend but admits to the threats against his friend. The ex-girlfriend told police that Bispo had never been aggressive with her.

Bispo’s mom was not just worried about the criminal charges. Her son had overstayed his visa and was now undocumented. She was worried immigration officials would find him. So she started a GoFundMe campaign to fight the criminal case. Jacques ended up contributing $5 to the campaign.

The Bispos say their lawyer told them that if they fought the charges and lost, Bispo could face five to 10 years in prison. He came to them with a proposal: Bispo would get probation. He would have to do community service and finish high school. And they said the lawyer told them that they wouldn’t have any immigration problems.

So after two months in an adult detention center, Bispo pleaded guilty to the charges, both misdemeanors. The teen was ordered to carry out the rest of his sentence at home on probation. “Only my son didn’t return home,” Bispo’s mother says.

She remembers waiting on a Friday, anxious for her son to call. She finally called the prison. Officials told her Bispo was already gone. Her worst fear had come true: Her son had been picked up by ICE.

Back in the Pacific Northwest, the region was simmering in the summer of 2020. The Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone, an occupied protest zone, rose and fell in Seattle. In Portland, agents with the Department of Homeland Security were deployed around the city to protect federal property. Thousands protested in the streets with nightly clashes between protesters and police.

In Longview, Washington, home of the Cowlitz County Youth Services Center, county commissioners received 200 emails that first week of July alone demanding that the contract with ICE end. Church groups especially were emailing and calling commissioners constantly, even leading a protest outside the youth detention facility.

Arne Mortensen stood by the contract he had inherited from previous leadership. But he was curious. In emails with local residents, Mortensen said that he wanted to learn for himself what was going on and that he was prepared to speak up about it if it caused more harm than good.

In August, Mortensen met with the American Civil Liberties Union of Washington, which argued that Cowlitz County was violating state law by holding youth on civil immigration charges. State law allowed youth to be held only for criminal reasons, ACLU officials said.

After the meeting, he emailed local court official Chadwick Connors to say he was surprised by what the ACLU told him: There were three teens being held at Cowlitz, one from Maryland, one from Texas and another from Oklahoma.

“I learned that none are there for criminal charges,” he wrote. “It is embarrassing to learn about your county from someone outside. Please tell me what you want to happen for this program.”

The following month, a local resident started a hunger strike in protest. At the Board of Commissioners’ meetings, residents showed up on Zoom demanding officials take action.

A reverend from the local Longview Presbyterian Church pleaded over email, “What can myself and other concerned citizens do to convince you to end this contract with ICE immediately?”

Officials were not moved. In public meetings, commissioners said youth were well taken care of and Cowlitz was a “safe haven” where the kids could avoid gang pressures. The facility was safer than going back home to their families, they said.

Then there was Commissioner Dennis Weber. “It turns out that those detained aren’t at all similar to the little children separated from parents at the border. They tend to be gang members – prone to violent activities,” he wrote in an email to one resident.

To another resident, he argued the youths were not really children and certainly not innocent. “We are not dealing with children. … I have yet to hear of anyone aligned with the ACLU advocating for the release of Kyle Rittenhouse,” he wrote.

Rittenhouse was charged with homicide in the shooting deaths of two people during Black Lives Matter protests after police in Kenosha, Wisconsin, shot and paralyzed Jacob Blake.

“A 17-year-old ‘child’ who had been living at home with his parents when arrested, separated from his parents, and accused of serious crimes in Kenosha,” Weber wrote. “Since when did the ‘American’ Civil Liberties Union stop advocating for Americans and switch to advocating for dangerous illegal immigrants?”

Local residents called out Weber, saying his comments were racist. He later apologized.

As the debate ground on, immigration attorneys decided to reach out to Dr. Amy Cohen to assess the kids. Cohen, a child psychiatrist with expertise in the detention of immigrant children, in turn submitted a signed declaration to commissioners in September.

She interviewed the children and found that “the long hours of solitary time produces depression and anxiety symptoms, especially for those with trauma histories, which are present for all youth in this population. The youth understand that any display of frustration or anger – verbal or physical – will be used against them as evidence that they are dangerous people.”

ICE’s internal records, provided to KUOW and Reveal, show that youth were disciplined for cursing or vandalizing their cells.

“Youth report never seeing psychiatrists for evaluation at Cowlitz despite being on psychotropic medications,” Cohen reported in her declaration.

“None could accurately report the names or doses of their medications.” Records show that among the 15 youth detained between 2015 and 2018, eight were placed on suicide watch while at the facility.

“I was appalled,” Cohen told KUOW and Reveal in an interview. “This was like a secret cache of children that no one knew about. Children who were locked away, really incarcerated in what were much closer to adult facilities. But most of all deemed to be dangerous without any of the burden of proof that would be necessary in either a criminal or juvenile court.”

Mortensen watched all this public debate and decided he wanted to gauge the truth for himself.

“If there was something we were doing evil, I definitely needed to find out,” he said in an interview.

In November, Mortensen emailed the detention officials with a request: “Would you be able to arrange for me a meeting with the ICE kids?”

For Kaio Bispo, Cowlitz holds some of the worst memories of his life. After ICE detained him in Georgia, he was transferred to another ICE contracted facility in Oregon. When that one ended its contract with ICE, agency officials moved him to Cowlitz.

“I hate that place,” he says. “I almost died there.”

The Cowlitz County Youth Services Center is surrounded by a barbed-wire fence. Youth are detained in single cells and spend around three hours in school daily. They don’t get time outdoors and are limited to an hour of gym time, according to Cohen’s report. In the evenings, some of the youth clean the facility, one of the youth said in a court declaration. During the pandemic, the facility conditions worsened. Classes, meetings with attorneys and counseling sessions ceased, according to court declarations and Cohen’s report.

“Sometimes I play cards with the guards,” reads one court declaration from a teen girl filed at the start of the pandemic.

“Because of the virus, they cleared all of the Washington State girls out of the detention center. … I have been here alone for over a month.”

In late September, Bispo started getting stomach pain. He alerted the staff but says they told him that he was just constipated. Instead, Bispo had the first signs of appendicitis. He ended up in emergency surgery after he started running a fever and vomiting blood. Bispo recovered but only after complications and weeks of hospital visits.

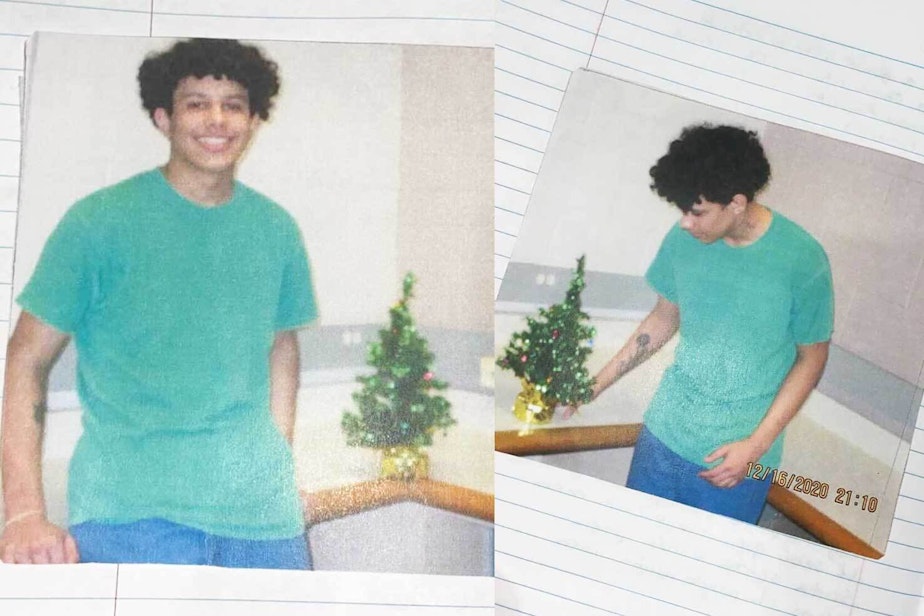

Several weeks after that experience, Bispo learned that someone wanted to meet him. A few days before Thanksgiving, Arne Mortensen walked into Cowlitz to meet him. Six feet apart from each other and masked up, they sat on opposite sides of a table.

Mortensen recalls the tension of the encounter.

“I’m an old guy. And he’s a young guy in a somewhat adverse environment. But I think we sort of broke that down,” he says. “I want to just talk to him as one human to another.”

Bispo remembers answering questions about soccer, school and what going home looked like. For a moment, he was hopeful. Mortensen asked Bispo’s attorney how he could help. They hoped Mortensen might provide a letter of support on his behalf that could be submitted to immigration officials. That could allow him to go home in time for Christmas, he hoped.

After the meeting, Mortensen wrote to Bispo’s immigration attorney: “I believe that it serves no positive purpose to keep your client in confinement; it is not good for your client and it is not good for the country.”

But instead of going home to his mom in Georgia, Mortensen suggested Bispo return to Brazil.

“I believe a ‘negotiated’ best outcome for all, given where we are, is to send your client back to his Father in Brazil. From there, your client can apply for immigration to the US via legitimate channels,” he wrote.

Bispo says he felt betrayed. He hadn’t been in touch with his father in years and his family was in the U.S. He was running out of hope and time. His 18th birthday was approaching.

Once he became a legal adult, he would be transferred to an adult detention facility in Tacoma, Washington. And on Christmas Eve, that’s exactly what happened. Bispo celebrated his birthday and was moved to the Northwest ICE Processing Center, suddenly one of the youngest people among hundreds of men. He could keep fighting his immigration case, but it would mean staying locked up.

During his time, he’d seen other youth in cases like his be detained for years only to be ultimately deported. Samantha Ratcliffe, who was Bispo’s immigration attorney, said she sees their spirit wane. “They start getting really hopeless, and they start seeing how the days go by and they’re still detained.” Some kids are forcibly deported, while others voluntarily leave as they lose their will to fight. “They don’t see light at the end of the tunnel,” Ratcliffe said.

Ultimately, Mortensen decided Cowlitz was an acceptable facility. While he prefers rehabilitative programs to detention, he said he wasn’t convinced it was the terrible “dog cage” local activists made it out to be.

As for Bispo’s emergency appendectomy, he shrugged it off, writing in an email that Bispo “looked healthy, moved well, and had good color.”

When asked directly about the youth’s medical treatment, Mortensen said Bispo “got treated quite nicely,” noting that in another less developed country, the teen could have died.

Mortensen had given Bispo a glimmer of hope and community members had thought he might be an ally in closing down Cowlitz. But he and the other county commissioners and judges continued to rebuff public pressure and stand behind the ICE contract.

Then, in mid-December, the state attorney general’s office got involved.

“The Attorney General’s Office is concerned that Cowlitz County operates a detention program for immigrant youth in violation of state law,” Chalia Stallings-Ala’ilima, an assistant attorney general in the civil rights unit, wrote in a letter to county officials.

“I request an opportunity to meet with you and your legal counsel to discuss the County’s compliance with the Juvenile Justice Act.”

The attorney general’s office argued that by holding youth for ICE, Cowlitz County officials were illegally detaining youth not for criminal proceedings, as state law dictated, but for civil charges.

Lawyers for the kids had been making that case for months, but now top officials in the state were taking note. County officials were on alert. An internal memo on a legal strategy circulated among commissioners, judges and the county prosecutor’s office, but officials denied KUOW and Reveal a public records request, saying it was privileged communication.

About two months after receiving notice from the state, Cowlitz County court officials emailed commissioners a press release that would soon circulate: The Cowlitz County Youth Services Center would terminate the contract with ICE. In it, court officials cited “increased lengths of stay not suited for our short-term facility, and because it’s clear the legislature intended to end contracts of this nature within our state.”

Court administrator and program supervisor Chadwick Connors declined a request for an interview.

“We have no additional information to share regarding the ICE contract,” he said.

The Washington attorney general’s office also wouldn’t comment.

“We couldn’t speak to what information the judges specifically relied upon in making their decision to end their contract with ICE. That’s a question best put to the judges,” a spokesperson wrote.

ICE officials declined an interview as well but said the agency is “currently reviewing its enforcement and detention practices, including options for the custody and supervision of different populations, including juveniles.”

For most of the youth, these changes came too late. During the reporting of this story, one teenager was deported to Guatemala and one young woman was released home to family in the U.S. after effectively being detained twice, once by the juvenile justice system and then again by ICE.

Once Bispo was transferred to the adult facility, he spent hours studying immigration policy and law. He’d decided to represent himself in his immigration proceedings. The last time he got a lawyer, it’d cost his mom nearly $10,000, and look where it had gotten him.

In the end, Bispo chose what’s called voluntary departure. If he’d been deported, he’d be facing a 10-year ban from being able to return to the U.S. If he decided to go back, he could at least in theory see his family again on a legal visa.

Adjusting to life back in Brazil is tough, Bispo says. It’s sometimes dangerous and the community where he is living is impoverished, but he’s working at a clothing store.

His mother and stepdad currently have a family petition pending to try to get him back to the U.S., but Bispo says he’s not banking on it. He thinks he could be a barber or work as a translator, maybe even go back to school.

“Sometimes I regret (it) because I should have just kept fighting my case,” he says. “But then it’s good because I’m free.”

Even though Cowlitz has ended its contract with ICE, the federal agency has found a new facility to do business with.

It now has a contract with a youth detention center in Winchester, Virginia.

This story was edited by Andrew Donohue, Laura C. Morel and Sumi Aggarwal and copyedited by Nikki Frick.

Follow Esmy Jimenez on Twitter: @esmyjimenez.