Her miscarriage in ICE detention raises questions about care

She wears a yellow uniform, loose, with a sweatshirt underneath. Her long hair, braided in tight cornrows near her temples. Her handshake, timid.

We talk in a small meeting room at the Northwest Detention Center in Tacoma, with her attorney and an interpreter.

Jacinta Morales was arrested by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents near her home outside Portland, Oregon, in April. Her experience raises questions about women in a growing detention system that’s used to mostly dealing with men.

Just 10 percent of people in immigration custody in the U.S. are women. But as the Trump Administration expands enforcement, more women are getting pulled into the system. Across the country, ICE arrests of women have climbed 35 percent in the first four months this year, compared to the same period in 2016.

For Morales, her time in custody is marked by deep loss. But it didn’t completely start that way.

“When I got here, they did a urine test and it came out positive,” Morales said through an interpreter. “I was thrilled to be pregnant and thrilled at the prospect of being a mother again and having Gonzalo’s baby.”

Gonzalo is her longtime partner. Medical records provided by ICE confirm the details of her care.

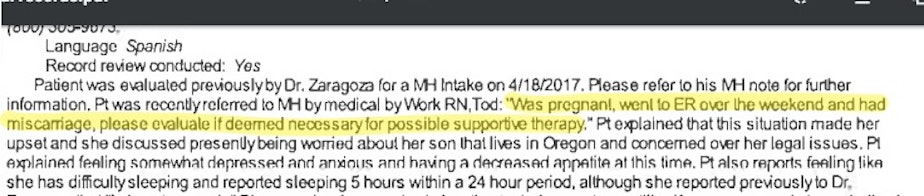

Morales had a prenatal appointment on April 18, a few days after her arrival. Her pregnancy was four weeks along.

Two days later, a doctor note describes her as doing well with “her greatest concern for being deported without her 11 year old son.”

Her son is a U.S. citizen. Gonzalo is caring for him now.

On April 22, medical records show Morales was cleared for travel. She learned she was on the flight roster for deportation.

“The day that ICE told me I would be leaving in a week’s time, I started to cry,” Morales said. “I had pains and felt nausea.”

She saw a doctor and said she felt better.

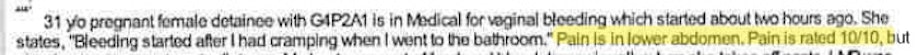

Then, a few days later, on April 29, Morales woke up bleeding.

“After an hour I went to doctor and they put me in a small room like this one, and I was really bleeding hard,” Morales recalled. “The officer asked me if I was feeling a lot of pain, and I said yes. And she said, ‘I’m going to go see if they can see you quickly.’”

Morales guesses she waited another hour, while other women were seen. She said one had a toothache.

In medical notes time-stamped around noon, Morales rated her pain 10 out of 10.

The doctor ordered a hospital ambulance. It was slow to come, so they took her in the back of a patrol car, sitting up, which she said made the bleeding worse.

At the hospital, Morales learned she'd had a miscarriage.

“My only consolation once I got out of this place was to have my baby,” Morales said. “Now I don’t have him. But I have another who’s waiting for me. That’s the only hope; the only thing I’m hanging on to.”

Federal policy

Morales’s situation raises questions about ICE’s policy concerning pregnant and nursing mothers.

An Obama-era policy, updated in 2016, says they will generally not be detained.

But new enforcement guidelines under President Donald Trump expand ICE’s reach and eliminate some old rules.

“In terms of her pregnancy, former guidance would have encouraged ICE to release her,” said Meghan Casey, an attorney with the Northwest Immigrant Rights Project.

As policies have shifted, Casey said it has created confusion about how ICE handles some categories of people such as dreamers and asylum seekers.

Casey, who represents Morales, said she was unclear how the new guidelines apply to pregnant women as she took up this case.

“I have requested her release on three different occasions essentially appealing to humanitarian factors in her situation and they have denied my request three times,” Casey said.

In an email to KUOW, an ICE spokeswoman confirmed that the 2016 guidelines for pregnant women are still current.

Under this policy, pregnant women can be held in detention for some criminal offenses, or if they’ve already been ordered deported. That could apply to Morales.

She was arrested for domestic violence a year ago, after police responded to a dispute with her partner, Gonzalo. That led to her immigration case. Then a judge ordered her deported after she missed a court date.

Morales said the notice went to the wrong address. She was arrested when she went to court to follow-up.

Women in detention

At the Northwest Detention Center, Morales struggles with depression. She barely leaves her dorm room.

“It’s a place I would not wish any woman to be in at all,” Morales said. “It makes you feel desperate. It’s very stressful — a lot of depression.”

Families at risk of deportation have generally thought of women and mothers as less targeted by ICE. But that idea has vanished under the Trump Administration.

In the first four months of this year, 292 pregnant women were held in ICE detention centers nationwide, accord to agency data.

“I would say they should take proper care of all pregnant women because I don’t wish what happened to me to happen to any other women.”

Morales knows miscarriages are common in early pregnancies; medical records show hers occurred at five weeks. Still, she wonders if more could’ve been done.

“I think if they’d been able to stop the bleeding, I think that perhaps they would’ve been able to save the baby, and I would have my baby.”

Some studies also suggest that stress and poor diet might contribute to miscarriages. A 2009 report from Human Rights Watch also raised concerns about medical care for women in ICE custody.

ICE policy details health care standards for women and calls for close monitoring of pregnant detainees.

“While detained, pregnant women will be re-evaluated regularly to determine if continued detention is warranted, receive appropriate prenatal care and be appropriately monitored by ICE for general health and well-being,” said Rose Riley, an ICE spokeswoman in Seattle.

In response to Morales’s emergency care on April 29, Riley said, “staff at the Northwest Detention Center followed ICE medical protocols providing an appropriate level of care given the results of on-site assessments of the situation.”

In June, an immigration judge granted Morales an unusually low bond of $1,500. It took her partner several weeks to raise the money with help from a local charity.

Morales is now at home with her son in Oregon. Her deportation case is still pending.