Garfield County pledges to keep jail shuttered after suicide went undetected

Family members of a man whose suicide went undiscovered in Garfield County Jail for 18 hours have settled their claim, in an agreement approved by a superior court judge on Monday. Kyle Lara’s parents say the most important part of the agreement has already occurred: the closure of the jail where he died.

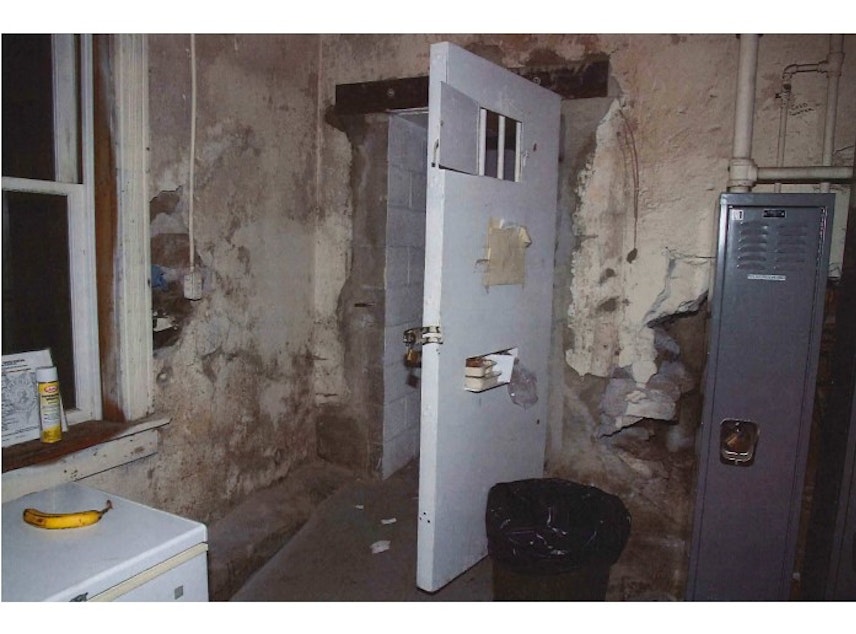

The family's attorney, Ryan Dreveskracht, said the jail “was so improperly run, the conditions of confinement were so egregious,” that Garfield County closed the jail in March 2023, shortly after the Laras’ tort claim was filed.

In a statement Drevesckracht said, “In addition to what is believed to be the largest municipal settlement for an in-custody suicide in state history, the Lara family negotiated a promise from Garfield County that its jail will not be reopened unless the county complies with state and federal regulations and the jail’s leadership and staff undergo state corrections training. Garfield County currently houses inmates in the Whitman and Walla Walla county jails.”

Garfield County officials said the Board of Commissioners couldn’t immediately respond to a request for comment.

Under the settlement, Garfield County also agreed to pay Kyle Lara’s parents $2.5 million, which David and Rhonda Sue Lara said will provide for Kyle’s 13-year-old daughter, their granddaughter, who they are raising.

Closing the jail “was what it was all about,” David Lara said, “to ensure this can never happen to another person.” But he said he still believes there was “no accountability” since no employees were penalized.

Sponsored

An investigation by the Washington State Patrol found that Garfield County placed Lara in solitary confinement despite indications that he was suicidal. People in detention were supervised by civilian 911 dispatchers who were busy with other duties, rather than by certified corrections officers. Staff failed to check on Lara when he blocked a video monitor with a sheet, and they continued to put meals through the slot of Lara’s cell door long after he was dead.

“I think about my son’s last day and when truly was the last time my son interfaced with anybody? How long was it?” David Lara said. “So to a certain extent, I’m very pleased that our city has taken the steps forward to correct these problems.”

But he said, “to this day I do not understand, there is no oversight whatsoever in the state of Washington of the jail system.”

Washington lawmakers have recently considered proposals to establish a new jail oversight agency, but so far they haven’t passed.

When he died, Lara was awaiting trial. He’d been arrested on suspicion of domestic violence after a fight with his girlfriend.

Sponsored

Rhonda Lara said her son struggled with addiction and, “he had been to some pretty rough places,” but she never expected their local town to pose such dangers for him.

“I’m the tough love mom that always said, ‘Don’t bail him out, he’s safer in jail if he’s going to be out doing whatever he’s doing,’” she said. “It’s hard for me to talk about because it really is the worst thing that’s ever happened to me in my whole life.”

She said it’s a relief to reach the settlement because now they can speak more openly with others in their small town of Pomeroy, especially about the need for more mental health care.

“I’m hoping to use our story as some kind of catalyst to get the community back together, to get them to understand what the real issues are here," Rhonda Lara said.

Rhonda and David Lara said their granddaughter is flourishing, and has benefitted greatly from working with a grief counselor. They said they hope this agreement will bring them some peace.

Sponsored

“It’s been over two and a half years since either of us slept,” David Lara said.

If you or someone you know is experiencing a mental health crisis or considering self-harm, call or text 988 for help. You can also contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255.