For orcas, the ocean is like a super loud upstairs neighbor

In Canada, the Port of Vancouver has ships slowing down through orca habitat. Now, some are hoping to do the same in Puget Sound.

Imagine you lived in an apartment where your upstairs neighbor blasted music 60 to 97 percent of the time, making it impossible for you to have a conversation, think, sleep, or listen to KUOW.

Southern resident killer whales live with this situation: Boat noise drowns out 60 to 97 percent of their attempts to communicate with each other and find food.

That’s because traffic isn't bad just on land in the Puget Sound area; it's bad at sea as well.

Puget Sound may not seem like a noisy place, said Scott Veirs, an oceanographer who studies killer whale acoustics. “When you go down to the beach, you hear the waves, just like we’re hearing here.”

Sponsored

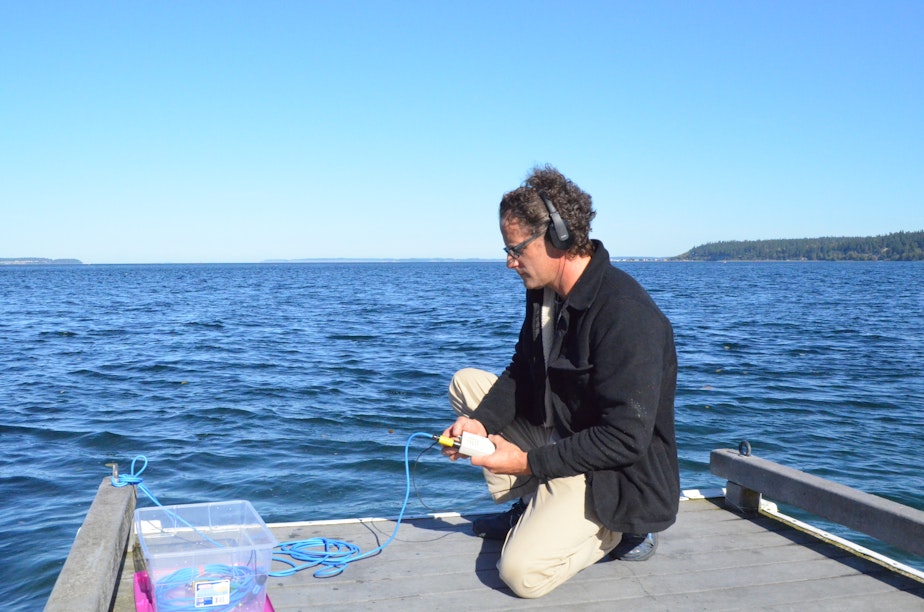

But, Veirs said, as he dropped an underwater microphone called a hydrophone off a dock into Puget Sound, “The ocean is a noisy place, particularly around here.”

“Sound is transmitted much more efficiently underwater," he explained. "For a typical ship going through Puget Sound, its sound is basically filling up this underwater canyon.”

And there are many ships: ferries, container ships, tankers, and fishing boats, pleasure boats, speed boats. Veirs said the biggest ships are the biggest culprits: cargo and container ships contribute about half the noise in Puget Sound.

That’s a problem for orcas. For them, noisy seas make the difference between finding salmon to eat and starving.

“Sound is the sense that’s most useful in the ocean,” Veirs explained. “The water’s typically pretty cloudy, so visual creatures like us don’t do very well. The creatures who are at the top of the food chain, like our local killer whales, are masters of sound.”

In other words, when whales can’t hear, it’s far worse than having a noisy upstairs neighbor.

“It’s truly life or death,” said Rob Williams, a biologist who studies how orcas respond to noise. “The stakes are not sort of peace of mind or quality of life.”

Williams said vessel noise makes it hard for orcas to hunt, because it seems to disturb them more when they’re foraging or eating than when they’re traveling or socializing.

It’s even worse when there aren’t enough chinook salmon to eat. In years when there are lots of salmon, whales go about their business no matter the boats. But in years when salmon are scarce, orcas stop hunting if their surroundings are noisy.

And if whales are not finding food, they die, Williams said, as we have seen in the Northwest recently.

That’s why, in recent years, the ports of the Pacific Northwest have started looking at ways to solve the problem of vessel noise.

On a clear day this fall, a bright pink container ship headed from the Port of Seattle to the open ocean. The pilot who navigated that ship through Puget Sound left the ship’s master with some advice about how to stay clear from orcas: Stay as far south in the shipping lane as possible.

Eric Von Brandenfels, the president of the Puget Sound Pilots, explained: “We show them the foraging area that lies around the southern coastline of Vancouver Island, and that it will be helpful … if they reduce speed and go along this traffic separation scheme.”

There’s no concrete incentive for them to do that — and yet about 90 percent of ship masters who visit Puget Sound participate.

“Mariners have, throughout history … had a love for marine mammals,” Von Brandenfels said. “It’s just always such a sight to see.”

On the Canada side of the border, the Port of Vancouver goes a step further and charges lower berthing fees to ships that slow down as they go through orca habitat.

That program has cut sound north of the border in half.

Researcher Rob Williams is finishing up an analysis of how the orcas responded to the slowdown; his results are due out in early 2019.

“This is a really hopeful environmental problem to work on,” Williams said. “As soon as you remove the sound source, the problem goes away.”

Williams said solutions include slowing ships down, recognizing shipping companies that quiet their vessels, and creating marine-protected areas where ships can’t go.

“If we can make it quieter, especially in the places that the whales are using to hunt,” Williams said, “we can buy the whales some time while we take really bold and dramatic action to recover chinook salmon stocks.”

This week, a task force is set to advise the governor how to help the orcas of Puget Sound. This is Part 1 of Orca Emergency, KUOW’s special series exploring some of the most difficult problems to solve.