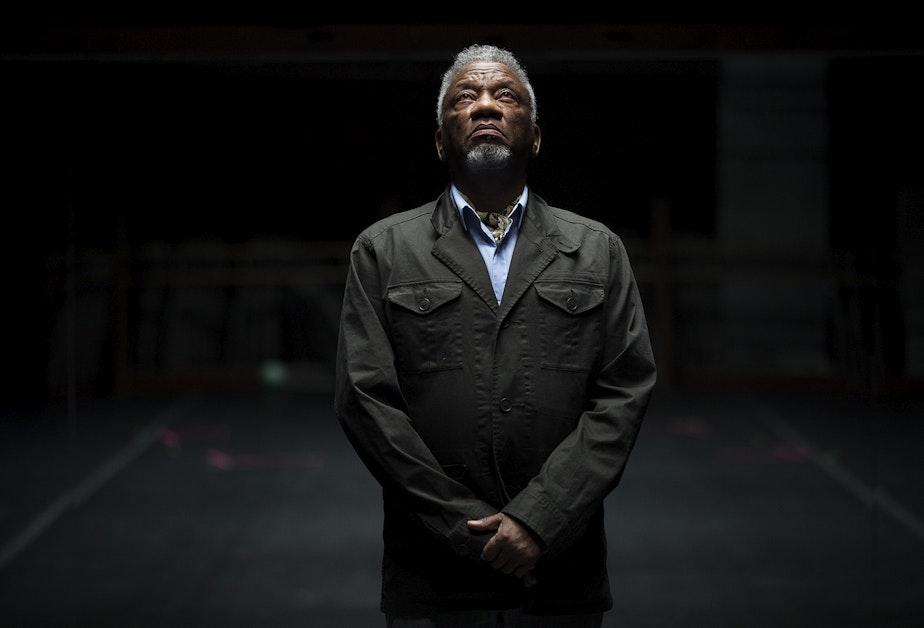

Transforming Black pain into beauty: The story of an Alvin Ailey protégé in Seattle

D

onald Byrd strides into rehearsal, black frame glasses sliding down the end of his nose. He takes off his shoes, walks to the folding table by the mirrored wall … and surveys his dancers.

He sits down. Opens his laptop. Byrd is neutral, neither mean nor chipper. He focuses his entire self on the dance, where toes are pointed, the emotion of the movement.

“Let’s run through the duets,” Byrd says, eyes on his laptop, searching for a music file.

The music begins, a slow, almost melancholy progression of chords, and two dancers wind sinuously around each other. They have the grace of ballet dancers, but this is no ballet. There are the classical steps, yes, but also sharper, staccato movements. Byrd stops them occasionally with suggestions—he cautions the duo to control the movement of their limbs, to lower legs more slowly to the floor. Watching him now, calmly guiding dancers through choreography, it’s hard to conjure the man described as sometimes too harsh, whose own personal journey has been turbulent … and also very lucky.

1 min

Fausto Rivera & Michele Dooley, Monday, September 17, 2018.

1 min

Fausto Rivera & Michele Dooley, Monday, September 17, 2018.

When Byrd arrived at Seattle’s Spectrum Dance Theater in 2002, he was an emigrant from New York’s high-octane contemporary art world, a scene that demanded all of his energy but provided little financial or emotional security.

Sponsored

At Spectrum, he became the leader of a community dance company that barely registered on the map. It was in a 90-year-old bathhouse on Lake Washington, for starters, a place where neighborhood kids learned jazz and modern dance.

Byrd has since transformed Spectrum into an internationally recognized contemporary dance company, presenting work that addresses the social and political concerns of 21st century America. His work also reflects his own story, which begins in the Jim Crow-era South.

Dance was not Byrd’s lifelong dream. He spent much of his boyhood in Clearwater, Florida, just outside of Tampa. After his mother remarried and moved to the Midwest with her new husband, Byrd stayed behind with his grandmother, who worked as a laundress and a domestic to support herself and her grandson.

“I loved that lady,” says Byrd. “She said to me that the first time she saw me, I was laying in the crib and she looked down at me and I smiled at her and she said, ‘I like this one.’”

Sponsored

Looking back at those years, Byrd believes his grandmother did her best to protect him from the racist attitudes and actions in Clearwater. He remembers his all-Black schools as refuges where nurturing teachers encouraged their students to succeed.

“I’ve heard people from there say, ‘Oh, your group did so well!’” he says. “And I think it’s because we had those Black teachers that were rooting for us.”

As a young teenager, Byrd was singled out as someone with the aptitude to move on to an Ivy League college. In 1967, he left Florida to attend Yale University on a scholarship. New Haven, Connecticut was like a slap in the face.

“The whole feeling of it was just like nothing I’d ever seen,” Byrd recalls. “Regardless of whether I was academically prepared, culturally I was definitely not. I mean, I had never been called the 'N word' to my face, but I got called the N-word in New Haven.”

Yale was still an all-male institution at that time, with students who’d attended elite prep schools. Even the other Black students Byrd met came from more privileged backgrounds than his own.

Sponsored

“In some ways, they were acclimated to operating in a predominantly white culture, as opposed to separate but equal,” he says.

Byrd stayed at Yale for just one year. In 1968, he transferred to Tufts University outside of Boston. He liked that it was co-ed, but he struggled to fit in. The clash between his personal background and his new cultural milieu would be the wellspring of his art.

1 min

Andrew Pontius & Nia-Amina Minor, Monday, September 17, 2018.

1 min

Andrew Pontius & Nia-Amina Minor, Monday, September 17, 2018.

This autumn Byrd and his dancers have been on a national tour, presenting a work Byrd created with theater artist Anna Deveare Smith, “Rap on Race.” The performance is based on a 1970 conversation between writer James Baldwin and anthropologist Margaret Mead, with dance interspersed throughout. In the original 2015 production, Byrd portrayed Baldwin.

Byrd gravitates to material that tackles race, class and politics. His dances have examined the social impacts of China’s Cultural Revolution and the Israeli/Palestinian conflict.

Sponsored

Byrd’s social agenda drew dancer Fausto Rivera to the company five years ago. Rivera considers dancing in these works to be his personal form of social activism, but he acknowledges it can be emotionally overwhelming. In 2015, Rivera, who grew up in the Kent area, performed in a revival of Byrd’s 1991 award-winning “The Minstrel Show,” featuring dancers in black-face makeup and woolly wigs, with Byrd reading audience-submitted racist jokes.

“It’s one of those shows where you were most conscious of the energy you’re receiving from the audience,” Rivera says. “It’s like, none, because they’re in a state of shock.”

“The Minstrel Show” wasn’t Byrd’s first, or last, foray into incendiary subject matter, but it may be his most overt commentary.

Sponsored

“It was disturbing,” Byrd admits.

In the original production, Byrd incorporated the transcripts of Clarence Thomas’s Supreme Court confirmation hearings.

“We literally took the transcripts and did it like a minstrel show, with tambourines.” “The Minstrel Show Revisited” added material from George Zimmerman’s arraignment in the Trayvon Martin shooting.

In 1992, the original “Minstrel Show” won a Bessie Award, the New York dance world’s top prize, but critical and audience response to the revival was mixed. The New York Times called it “overly long” and “repetitive.” Despite the rise of Black Lives Matter and renewed public discourse about racism, the world seemingly wasn’t ready for Byrd’s updated take on race in America. Seattle choreographer Jade Solomon Curtis, who danced with Spectrum from 2012 to 2016, believes Byrd’s work is ahead of its time.

“It’s not Disney, it’s not a whimsical way of experiencing the world,” Curtis says. “He’s going to make it real, and people oftentimes aren’t ready to experience that when they want something that just makes them feel good.”

If Byrd’s work can be tough; so can his manner. He has a reputation for burning through talented dancers, being verbally abusive, even misogynistic. Solomon Curtis has heard all the criticisms.

“I feel both sides,” she says. “But it’s kind of like family. I can talk bad about my family but you better not. I have definitely experienced all that, but the positive things overshadowed it, which is why I stayed.”

Byrd has had both supporters and detractors over his long career. As his star rose on New York’s contemporary dance scene in the 1970s and 1980s, other choreographers found him arrogant. Byrd believes what some see as arrogance is really him standing back and observing. He traces this back to his days at Yale, where the strangeness of his surroundings pushed the heretofore gregarious young man to stop talking. He didn’t think he was better than everyone else; he just didn’t understand them.

Byrd immersed himself in literature, music and theater. He took ballet classes, mostly to impress a young woman he had met. Eventually a friend recommended that Byrd see the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater when it toured in Boston. That performance changed his career trajectory.

Like every Ailey performance, the show ended with the company’s signature work, “Revelations,” a dance set to traditional Negro spirituals. It moved Byrd to tears.

“What Alvin Ailey had done was transform the pain of slavery into something that was magnificent and beautiful,” he said.

Several years later, Byrd moved to New York City and enrolled in the new Ailey school.

Sylvia Waters, who danced at Ailey, recalls Byrd as a skinny young man with a unique way of moving. He stood out among the larger, stronger dancers in the school. Waters thought he might bring something special to the Ailey company, but Byrd was drawn to New York’s burgeoning contemporary dance scene, to choreographers Twyla Tharp, Merce Cunningham and Paul Taylor.

Waters kept tabs on Byrd, and almost a decade later, was there when his career flamed out.

B

y 1985, Byrd’s dance company, Donald Byrd/The Group, was earning rave reviews in New York. But his late night partying and drug abuse had begun to encroach on his art, and his relationships.

“I did some shitty things in order to get money,” Byrd says.

He moved in with a drug dealer, then stole drugs from him. Byrd promised to create dances, then failed to deliver; he set up meetings but didn’t show up. He finally hit bottom during a high-profile show at New York’s La Mama theater.

“It was awful,” he says. “People liked my dancing, but most of the time I was so high I couldn’t even feel my limbs. Half the time I was saying, ‘Please God don’t let me break my neck,’ because I couldn’t feel anything.”

Ultimately Byrd checked himself into a residential drug rehab program.

A year later he was back in New York, trying to reassemble the life he’d left in shambles. He attended daily 12-step meetings and therapy sessions; he also went to as many dance classes as he could. He had time to fill; none of his former dance colleagues would take his calls. Finally, an old friend hired him to teach a summer workshop; slowly Byrd found the confidence to start choreographing.

One day, an acquaintance mentioned that Sylvia Waters was looking for him; Byrd was surprised. He’d stood her up during his most drug-addled days. But Waters didn’t know about the drug problems; she loved Byrd’s approach to choreography.

“It was athletic and there were no rules,” Waters says. “If there were rules, they weren’t rules I was familiar with.” She invited Byrd to make a dance for Ailey’s second, developmental company.

As he set to work on a dance he called “Crumbs,” Byrd attracted another fan.

“Alvin (Ailey) would come in and out of the room,” Waters says. “One day, he said, ‘I like what this young man is doing. I’m going to write a grant for him to make work on the first company.’”

That dance, ‘Shards,’ became an internationally acclaimed success. Byrd’s star rose again.

1 min

Mikhail Calliste & Michele Dooley

1 min

Mikhail Calliste & Michele Dooley

Donald Byrd’s tenure in New York has been well covered. Ailey continued to commission his work. After the Bessie award — the dance equivalent of a Tony — for “The Minstrel Show,” Byrd scored another hit with “Harlem Nutcracker,” a riff on the classic holiday ballet. But critical success and audience acclaim don’t always equal financial stability or professional satisfaction. Byrd was getting more work, but he wasn’t happy doing it.

“Mostly because it was work that was kind of feeding the machine,” he says. “I was just bored with it.”

And his dance company still had money problems. Things got worse after 9/11. Arts groups across New York were hit financially. It was the last straw for Byrd; he shuttered his company. Several people-including Pacific Northwest Ballet co-artistic directors Kent Stowell and Francia Russell—suggested he apply for the job at Spectrum Dance Theater.

W

hen I think of Donald Byrd’s life, I imagine him as a salmon swimming upstream through unfamiliar waters, searching for the safe river bed that spawned him. The Northeast certainly was strange territory for the young man from Florida, but the Pacific Northwest was even farther afield.

“Where’s all the Black people at?” he wondered when he first arrived; African Americans still make up only about 8 percent of the city. Even after 15 years in Seattle, Byrd still isn’t totally at home.

Meanwhile, when he first stepped in to lead Spectrum, it was nothing like the New York dance companies he knew.

“It was kind of like a parks and rec situation, although the adult jazz classes were very serious,” Byrd says. What attracted him was Spectrum’s commitment to access, as exemplified by a comprehensive youth scholarship program.

The artistic going wasn’t easy; long-time Spectrum fans were put off by Byrd’s issue-themed dances. The professional company members balked at his stringent technical demands. But Byrd persisted in his vision of a multi-racial troupe that featured both choreography and artists of the highest caliber. He wanted the young dance students to see that they, too, could make careers in the field.

Dancer and choreographer Jade Solomon Curtis says, while frequently frustrating, her years with Byrd were also inspirational.

“It’s given me the courage to make the kind of work I’m making, and to not budge on how I’m willing to present that work.”

Donald Byrd has woven himself into the fabric of Seattle’s vibrant arts community. He’s served on the city arts commission, choreographed for local theater and opera productions, and he initiated a showcase for emerging Black choreographers.

As he nears his 70th birthday, Byrd isn’t slowing down. His new artistic season will feature the premiere of a dance version of Tchaikovsky’s “Iolanta,” as well as “Strange Fruit,” an homage to Billie Holliday’s classic song about lynching.

Byrd is less ambivalent about living in Seattle than he once was; he can’t imagine returning to his childhood home in Clearwater, Florida.

“When I went back to my community, I didn’t feel part of it anymore,” Byrd says. “I say that my family, they sacrificed me for something they aspired to. I wanted those things, but I feel like in the process of doing that, I lost some of myself.”

Byrd hasn’t rediscovered that self in Seattle, but he has found the freedom to work outside the glare of the New York critical spotlight.

“I was confronted with whiteness, and in a way, that was overwhelming,” he reflects. “I added some color, literally and figuratively.

“I think being here liberated me,” says Byrd.