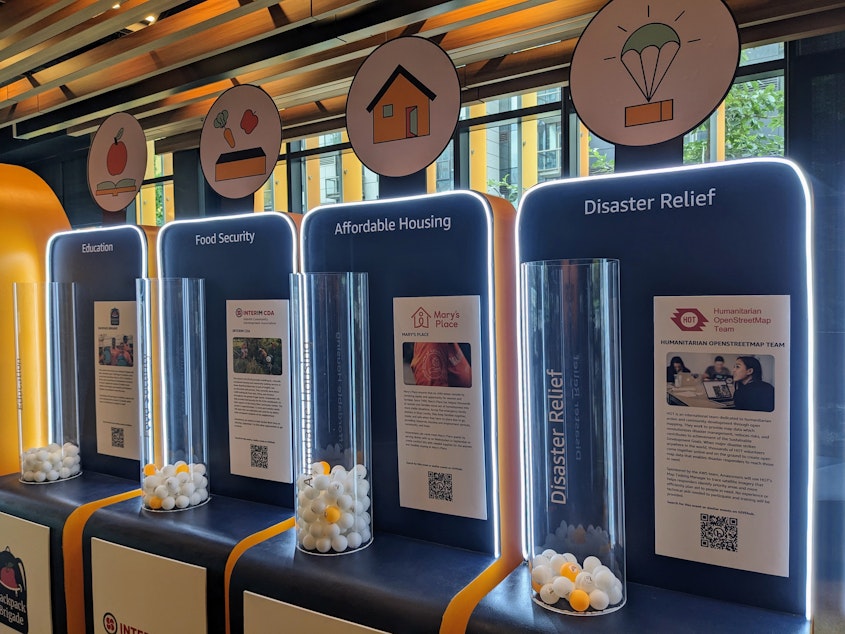

Disaster relief delivered by Amazon

A

be Diaz has a lot of Slack channels open on his computer. But unlike other office workers, they aren’t dedicated to watercooler chats or work deadlines.

The channels correspond to disasters making headlines around the world: the devastating wildfires in Maui, the fallout from Hurricane Idalia in Florida, the massive Gray Fire north of Spokane, and the counteroffensive by Ukrainian troops after the Russian invasion.

Diaz is the head of Amazon Disaster Relief, a team dedicated to donating Amazon's vast resources to respond to catastrophes. From his cubicle in Seattle, he fields requests for help from all over the world.

Amazon is spearheading a growing trend in the private sector. In 1990, less than 20% of the world's largest companies participated in disaster relief. Today, more than 95% of the top 500 U.S. companies are doing this work. Amazon alone says it has donated 23 million items since launching its disaster relief program.

With natural disasters becoming a nearly constant phenomenon, government aid resources are stretched thin. Companies like Amazon are stepping in to provide relief, using the same expertise that allows packages to arrive on your doorstep hours after you place an order.

Sponsored

Experts agree that the private sector has become a crucial partner in disaster relief. But what it means to become increasingly reliant on corporate relief to help out after the storm remains an open question.

O

n an early September day in Seattle, Diaz deploys resources to communities impacted by the wildfires in Maui and Hurricane Idalia in Florida.

“Hawaii — as they should for remote islands — they don't want to have single-use plastic,” he said in an interview at Amazon’s headquarters. “So for me to send food clamshells, they need to be compostable. They need to be biodegradable. We're able to tap into not just our selection, but the expertise of many of our people in the company, like vendor managers, to say, 'What is the right product for us to send to that location?'”

The first Amazon Air relief flight landed in Puerto Rico in 2017, two weeks after Hurricane Maria hit. Diaz is from Puerto Rico, and still has family there.

Sponsored

“I understand what that feels like,” he said. “I know how it feels to get your house flooded. I know how it feels to see your community impacted by it. Obviously, there's a personal connection.”

When Hurricane Fiona hit Puerto Rico last year, Amazon was on the ground in less than half the time it took in 2017. That's in part because Amazon now has a warehouse in Atlanta dedicated to emergency relief. It's full of diapers, tarps, solar chargers, and other supplies ready to ship out when a disaster strikes. Diaz said in many cases, Amazon supplies are the first to arrive in the wake of a storm.

Amazon is uniquely positioned to do this kind of work. It has warehouses around the world, stocked full of emergency supplies. Amazon also has satellites that map changing conditions on the ground in real time and an international fleet of airplanes and delivery drivers with access to those maps. Plus, Amazon has a sprawling public policy team, with direct lines to mayors and other decision makers in most major cities. It’s hard to imagine a government with comparable resources.

Sponsored

“The same efficiency that you see on your normal Amazon orders at home, that's what we want or better for when we're responding to disasters,” Diaz said.

There’s no doubt Amazon is fast and well-resourced, but there’s a reason government moves more slowly. There are mechanisms in place to hold government agencies accountable.

“We create recovery for a society that has been affected by a disaster, so we want to ensure that the resources are well spent, and then that society recovers in an efficient way,” said Luis Ballesteros, a professor at the University of Boston whose research focuses on corporate disaster relief.

Ballesteros says that because corporate disaster relief is new, society hasn’t caught up with a system of accountability.

“Corporate disaster philanthropy is one of the fastest, if not the fastest-growing type of philanthropy at the international level… despite this frequency, there's very little understanding of how to do it,” he said. “We need to have a balance, and this is not really well understood. It means that we really don’t know what the role of companies should be.”

Sponsored

Still, Ballesteros says corporations have a vital role to play as the severity and frequency of disasters increases. And according to his research, corporate disaster relief works.

Several of his studies have shown that countries receiving substantial donations from the private sector recover faster than countries that get other types of aid. Recovery is measure by factors like educational attainment, life expectancy, and growth in the decade following a disaster.

Ballesteros is also working on new research that shows companies that do disaster relief see a boost in employee productivity. He says that’s because employees are more motivated when their employers are helping with major disasters.

“We can have a cynical approach about this,” he said, when asked whether there’s a business case for corporate disaster relief. “But in reality the complexity of disasters requires a multi-state stakeholder approach. This is true everywhere, even in developed countries like the United States."

EDITOR'S NOTE: This story has been updated with additional context on companies providing disaster relief.