Despite opioid epidemic, drug court enrollment is down. King County hopes to change that

King County’s Drug Diversion Court is celebrating its 30th anniversary. It was one of the first programs in the nation to help people clear their criminal records, if they enter treatment and stop using drugs.

But amidst the opioid epidemic, drug court enrollment has shrunk in recent years. This month partners including police and prosecutors have agreed to broaden eligibility and access.

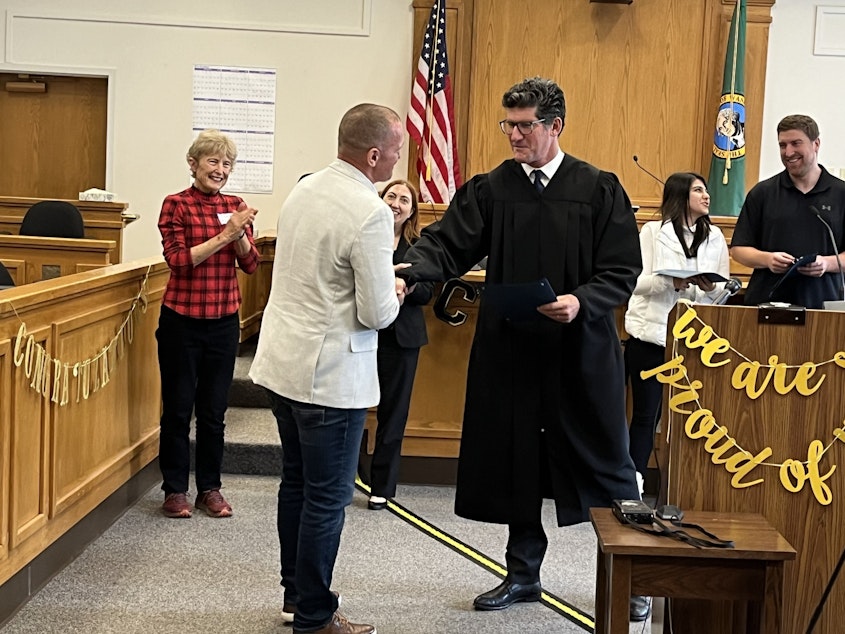

At a recent drug court graduation, “Pomp and Circumstance” played on the speakers as three graduates took seats in a King County courtroom in downtown Seattle.

Family members, case workers and other supporters cheered them on. The atmosphere was festive, but graduates like Brandon Wright made clear, they’ve been through a lot to get here.

“I got real honest with myself,” Wright told those gathered in the courtroom. “I recognized what I needed to work on, and I got to work on that.”

Participants aren’t enrolled in drug court over drug possession, which is now a misdemeanor. They typically face multiple felony charges, often for property crimes related to their addiction. Certain charges are eligible only if victims give consent.

Participants commit to a rigorous program — including random drug tests for roughly a year — to get their cases dismissed on graduation day.

Sponsored

King County Superior Court Judge John McHale explained that drug court provides free residential treatment, housing, cellphones, and case managers along the way.

“I’m very proud of this program and I’m proud of the successes,” McHale said. “As a judge in this program, I have more resources available to me than I have in any other assignment or that any other judge in our court has.”

Despite current concerns about crime fueled by addiction, and calls for more treatment and resources, drug court managers say their program is underutilized and has room to spare.

Drug court graduations in King County are just half of what they were five years ago. There were 109 graduates in 2019 and the same number in 2020. In 2023 there were 55.

Leandra Craft is a senior deputy prosecutor with the King County Prosecutor’s Office and heads the unit that includes drug court. Craft said these days there are fewer eligible cases overall. Understaffed police departments are focused on addressing violent perpetrators, who aren’t eligible for drug court. And some people will choose a shorter jail stay over an abstinence-based recovery program.

Sponsored

“There are a number of people that are coming through the criminal legal system that are not necessarily ready to address their behavioral health concerns, or they’re not ready to move on to a life of recovery,” Craft said.

Partners in drug court say the recidivism outcomes make it an important option. Program Manager Christina Mason said they follow each participant for three years.

“Ninety percent of our participants have no new felonies and 73% have no new crimes at any level, including misdemeanor,” in that timeframe, she said.

This month, stakeholders, including police and prosecutors, agreed to expand the drug court’s eligibility to include a more serious charge — robbery in the second degree, like using physical force to shoplift or snatch someone’s cellphone.

Sponsored

There may be more strings attached for those participants — some of them won’t get their cases dismissed. Craft said those defendants will plead guilty but to a lesser charge. If they graduate, they will likely avoid additional prison time.

“They would leave graduation with a conviction, but no time in custody to serve,” she said.

Stakeholders also agreed to remove “most criminal history disqualifiers” (except offenses already excluded from what are generally known as "therapeutic courts" under state law) and increase the amount of restitution that eligible participants may owe from $7,500 to $10,000. There’s also public funding to pay that restitution.

“We do have potential participants and family members in the community calling our office to say, ‘I need help’ or, ‘My son or my daughter or my loved one needs help, please can this person access drug court?’” Mason said.

Sponsored

She said the eligibility changes will allow them to say yes more often. But no one has any estimates for how much enrollment might increase.

Mason said drug court is currently serving 114 participants on any given day, and each participant needs more intense services than they required five years ago. But she estimates that the program could currently accommodate up to 200 participants right now.

Joe Barsana is the drug court’s housing case manager. He’s also a drug court graduate himself. He displays his own harrowing sequence of booking photos, taken back when he was caught in the cycle of addiction and arrest.

Barsana said the strict routines and generous supports of drug court were what he needed to be successful.

“I found out that I’m not Joe who continued to use heroin, fentanyl, and methamphetamine on the streets," he said. "I’m not the Joe who continually got arrested and booked and released. I’m Joe who’s a good uncle today, I’m Joe who’s a good employee today.”

Sponsored

Barsana said graduation from drug court can be a precarious moment, when all that support starts to wind down. So, he recently started a new organization, the Washington State Therapeutic Court Alumni Association, to give graduates an ongoing community.

“After you graduate from drug court, welcome to the club. Welcome to alumni. Where we’re going to be here to be able to support you,” he said.

Barsana said he found fentanyl addiction to be completely different from other drugs. He spent nine months in residential treatment as part of his recovery, and actually took part in the drug court program twice, facts he hopes will reassure and inspire future drug court participants.

“We’ve seen the worst,” he said. “But once we start rebuilding our lives, there’s an empowerment and a fire inside that we really can’t describe.”

Stephone Adams graduated from drug court in spring of 2023. He’s currently living with his family in Bremerton, and commuting by ferry to work in Seattle. His daughter is just turning 4.

“I’m doing great!" Adams wrote in an email. “If it weren't for the guidance of drug court I wouldn't be the dad, husband, and son I am today.”