Cancer risk can lurk in our genes. So why don't more people get tested?

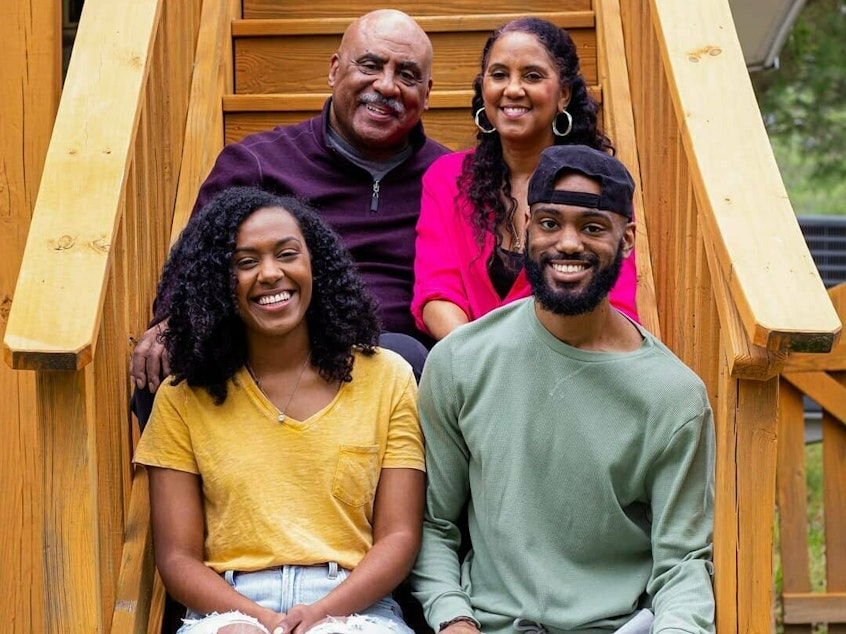

A few years ago, Junius Nottingham Jr. was on a family vacation in Florida with his wife, his daughter and his son, Jeremy. Jeremy was 28 years old, over 6 feet tall and athletic. He had followed his dad into law enforcement and had already built a career working for federal agencies, including the U.S. Secret Service.

"Jeremy told my wife that when he has a bowel movement, he bleeds a lot," Nottingham recalls. "And so my wife says, 'It's probably hemorrhoids. When you go back to Birmingham, Alabama, go see your doctor."

His son did, and his family was blindsided by what happened next.

"We get a call the day after Jeremy went back saying that Jeremy had Stage 4 colon cancer," says Nottingham. "My wife and I are looking at each other like, 'What? What's going on?'"

Unbeknownst to them, members of the Nottingham family have a genetic variant that confers a high risk of colon cancer and other types of cancer. And in this, they're not alone.

Sponsored

Cancer is the second leading cause of death in the United States, and about 10% of it is thought to come from inherited genetic mutations that increase risk.

Experts say that millions of people in the U.S. are walking around with a genetic variant that raises their risk of developing cancer. The vast majority of them have no clue.

That's a problem, because people who know they're at a higher risk for certain cancers can take action, like going for more frequent screening tests such as colonoscopies and mammograms or even having preventive surgeries.

A simple, relatively inexpensive blood test can now check dozens of genes associated with different kinds of cancers — cancers of the breast, ovaries, colon, pancreas, stomach, prostate and more.

But experts say that most people who should be offered this kind of genetic screening for inherited cancer risk never hear of it.

Sponsored

"It's an amazing scientific advance. And it's a shame that it's not being used as widely as it could be to realize its full impact," says Sapna Syngal of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

"A tough pill to swallow"

Nottingham, for example, had a mother and a grandmother who had both died of ovarian cancer. But it was only when his son, Jeremy, was diagnosed with colon cancer that doctors suggested genetic screening for his family.

"We're told we all have to get tested for something called Lynch syndrome," Nottingham says. "I had never heard of Lynch syndrome in my life."

Lynch syndrome is an inherited genetic condition that comes with up to an 80% chance of developing colorectal cancer, plus an increased risk of cancer in other organs.

Sponsored

"That's a big deal," says Lisa Schlager, vice president for public policy at a group called FORCE (Facing Our Risk of Cancer Empowered) — especially considering how many people may carry a mutation linked to the syndrome. "It affects 1 in 300 Americans."

She notes that Lynch syndrome is more common than cancer-causing variants in two genes linked to breast and ovarian cancer, BRCA1 and BRCA2, which have gotten a fair amount of public attention.

In 2013, for example, actress Angelina Jolie went public with her family's BRCA1 mutation and her decision to have preventive mastectomies to reduce her cancer risk.

Genes linked to other kinds of cancers haven't been as widely publicized.

"We've discovered in recent years that there are many, many other mutations that cause increased risk of cancers," says Schlager, adding that there are about two dozen genes with cancer-related mutations that are "pretty common."

Sponsored

When Nottingham got tested in the wake of his son's cancer diagnosis and learned that he had a Lynch syndrome mutation, presumably inherited from his mother, it was a terrible realization.

"My son has Lynch syndrome, and I gave it to him," says Nottingham. "That's a tough pill to swallow."

Having this genetic variant meant that he also was at significant risk of cancer. His doctor insisted that he get a colonoscopy. Nottingham remembers the fog of coming out of anesthesia.

"I'm trying to wake up, and Dr. Brown is like, 'You have cancer — you have to have surgery,'" recalls Nottingham, who couldn't believe that he also had colon cancer. "I'm like, 'This is a bad dream.' You know, I go outside, I tell my wife and our world turns upside down, again."

"There's dramatic undertesting"

Sponsored

A decade ago, genetic screening for inherited cancer risk cost thousands of dollars. As a result, physicians were more selective about who got referred for this testing.

In recent years, though, the cost has come down dramatically.

"It's a much more reasonable price," says Tara Biagi, a genetic counselor with MedStar Georgetown University Hospital.

She explains that these days, the out-of-pocket cost for someone without insurance could be around $250, "rather than $4,000, which is what it used to be." People with insurance might pay nothing or just a copay.

Testing is also more informative, as labs can now check a slew of cancer-linked genes at once.

Health insurance providers have loosened their restrictions on whom they will cover for this kind of testing, which means more people than ever have access.

Nonetheless, "most people that should be getting the test are not," says Dr. Tuya Pal, a clinical geneticist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

It has been about three decades since the discovery of BRCA1 and BRCA2, she says, "and we still have only identified a fraction of the adult U.S. population that's at risk. A lot of people that are at risk remain unidentified."

Researchers estimate that about 5% of people living in the U.S. have one of the known genetic mutations that can significantly increase cancer risk, says Allison Kurian, a cancer physician at Stanford University.

Similar to Junius Nottingham, those who know they have a cancer-related mutation often had a relative with cancer who got genetically tested and then told family members that they should be tested as well.

The trouble is that most people diagnosed with cancer never get tested.

Kurian and some colleagues recently did a study looking at over a million people diagnosed with cancer in Georgia and California. Only 6.8% of them got tested for inheritable genetic variants linked to cancer — which Kurian says is almost hard for her to believe.

"Because we did the study, I know the data are accurate," says Kurian. "It's just that, unfortunately, there's dramatic undertesting going on."

If doctors were following the latest expert guidelines, they'd offer testing to everyone with ovarian cancer, pancreatic cancer, metastatic prostate cancer and male breast cancer. And they'd consider offering it to everyone with colon or breast cancer.

Yet Kurian's study found that less than half of ovarian cancer patients got the testing. People with other cancers were even less likely to get it.

One recent study looked at how many cases of hereditary cancer syndromes would be found if doctors did genetic testing in just every patient with cancer. Researchers performed the testing on nearly 3,000 patients with all kinds of solid tumors, regardless of their age or family history.

"Nearly 1 in 8 patients had a cancer predisposition gene," says Dr. Jewel Samadder at the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix.

In addition to alerting family members that they could be at risk, he says, knowing that information frequently helped people choose the best treatment for their own cancer.

Instead of just having a lumpectomy, for example, a patient who learned she had a mutation in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene might choose to have a bilateral mastectomy.

"Doctors are not up on this"

Asked why so few people get tested, both researchers and patients say that many cancer doctors aren't familiar with the latest research on inherited risk or that they don't know the cost of testing has dropped.

"That is not a problem in the major cancer centers. But most people get treated at a smaller or regional center, and those doctors are not up on this or aware of it," says David Dessert, a long-term survivor of pancreatic cancer who has a BRCA2 mutation.

Samadder says that even at a major medical center, not every patient with ovarian cancer gets referred to genetic counseling, even though that national guideline has been in place for years.

The number of gastroenterologists thinking about genetic testing or getting a complete family history for colon or pancreatic cancer "is far below what it should be," says Syngal. "The awareness still is very low."

Another problem is that patients or their relatives don't know to ask their doctors for this testing.

Some people may not even realize that they have a family history of cancer, because past generations often kept cancer secret.

"You didn't want to talk about cancer in the family. You didn't even want to mention the 'C-word,'" says Dr. Susan Klugman, president of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. "So therefore their descendants may not know: Did they have ovarian? Did they have cervical cancer?"

Then there's the fact that people, including some doctors, may not appreciate that hereditary cancer syndromes can raise the risk of cancer in multiple organs.

Junius Nottingham, for example, didn't know that ovarian cancer in female relatives meant that he might be at a higher risk of colon cancer.

Klugman recently saw a patient who had uterine cancer a couple of decades back. That patient now has rectal cancer.

"If someone who had seen her, even her internist, said, 'Hey, you had uterine cancer at age 49. You should see genetics. You should get testing,' we might have caught that rectal cancer a lot sooner," says Klugman, because if this patient had Lynch syndrome, she would have gotten frequent colonoscopies.

The colonoscopy that Junius Nottingham had after getting genetic testing caught his colon cancer at an early, treatable stage.

Unfortunately, his son Jeremy's cancer was more advanced and ultimately didn't respond to chemotherapy. He died in November 2021.

Nottingham, who is stricken with grief, is now doing everything he can to raise awareness of hereditary cancer risk, to try to spare others the pain that he feels every day.

"If there is any history of cancer in your family, any history," says Nottingham, "go get genetically tested." [Copyright 2023 NPR]