A Seattle teen quit smoking fentanyl. Every morning he thanks God he’s alive

“I spent a lot of time thinking that I was the cool guy,” he says, sitting on his parents’ couch in northwest Seattle. “But now I go get a shot in my butt every month and I go to AA, you know what I mean? It's humbling.”

Elias Hansen looks sharp since he got off fentanyl this fall. He’s got new gold chains, designer jeans, and white Nike Air Force 1 sneakers.

No big deal for some, but a huge deal for him.

“I didn’t spend the money I spent on those on drugs,” he says.

Earlier this year, Elias was smoking fentanyl pills – powerful, illegal opioids that are more addictive, and more dangerous, than heroin.

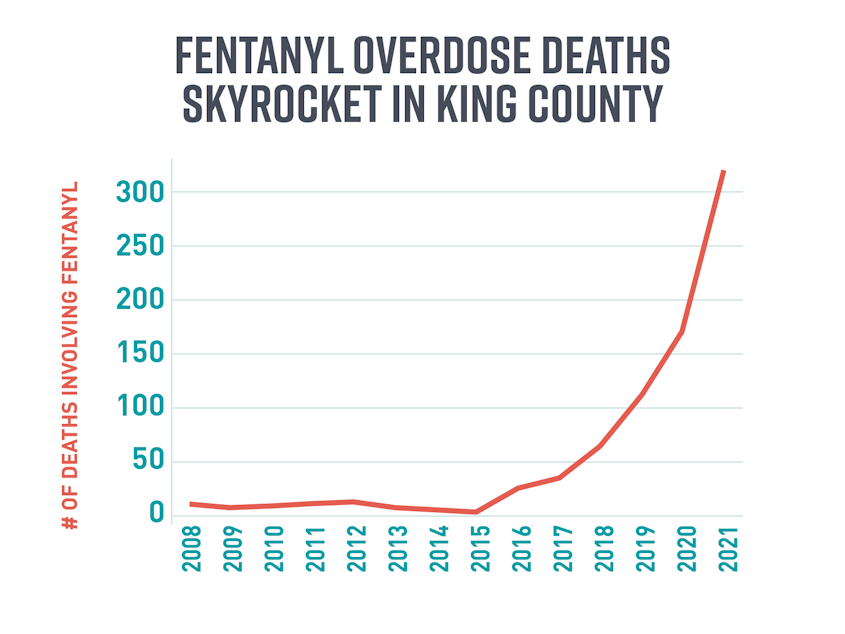

Those little blue pills have flooded the local drug market. And they’re contributing to a record number of overdose deaths this year in King County.

Sponsored

For Elias, addiction was grueling and traumatic.

“I legitimately would wake up every morning and be like, ‘Why the fuck am I not dead?’” Elias says.

Before fentanyl, he had a long history of drug use, starting with cigarettes at age 11.

Then it was beer, followed by Xanax a few years later, and marijuana.

Sponsored

Elias says he wanted to feel cool. More importantly, NOT feel anxious.

“There's tons of pictures of me when I was maybe like, 3 or 4 years old, where my eyebrows always furrowed,” he says. “Always very concerned about what's going on.”

When he drank alcohol, that pressure lifted. “I wasn't worried about the kids at school making fun of me,” he says. “I was just happy.”

When life got hard, he hit the substances even harder. About a year ago, around New Years, he was depressed and started drinking heavily and smoking heroin.

Soon, fentanyl entered the picture, too, when he was hanging out with friends who were smoking a fentanyl pill, also called a perc.

Sponsored

"They're like, ‘Dude, there's a perc right here.’ I was like, ‘No, I don't want to start the fentanyl stuff you know, heroin’s already enough.’” But he gave in. “Then I was just like, ‘You know what? Fuck it,’” he says. “I'm already doing heroin. You know? It can't be that much worse. So I got really high.”

He felt like he was in a trance as he walked to a public park and sat there with his friends. “I was absolutely in heaven,” he says.

Elias smoked the next day, and the next day he found himself a dealer (aka a “plug”) and paid $20 a pill. He drained his savings from a previous job and started stealing.

The pills were all too easy to acquire – just take the bus downtown – and eventually he found them for half the price.

He says the high was fantastic – even just itching his nose. "It’s better than getting a hug from your mom, it’s better than having sex. It's better than eating good food,” he says.

Sponsored

Hours later, the fallout was excruciating.

“Opioid withdrawals are, number one, very emotional,” Elias says. He felt like he had a fever. “I just was super, super, super cold. And it felt like my bones were trying to come out of my body.”

He kept yawning.

“That's a big thing for parents, watch out if your kid’s yawning like two times a minute, check in on them,” he says.

Elias never overdosed but knew other kids who did, including a close friend. He worried about how own death all the time.

Sponsored

"I never wanted my pops to find me dead,” he says. "You're watching people overdose, you can imagine yourself overdosing pretty easily, right? When he was a kid, Elias’s parents teased him because he couldn’t get away with trouble. He wasn’t a “smooth criminal,” they said.

After their son got heavily into drugs, Jenny and Nathan Hansen were surprised.

“We didn't have any idea of how much, or what kinds of drugs he was starting to use, and how early,” Nathan Hansen says. “He did a pretty good job of concealing it.”

Until the smell of burning plastic wafted up from the basement. "I kept getting this weird whiff,” Nathan Hansen says.

Jenny Hansen thought something was burning on the furnace. It took them a while to realize it, but it was the smoke from burning fentanyl pills. In retrospect, Jenny Hansen is ashamed how “clueless and Naïve” she was, she says. She only thought to be on the alert for the smell of weed and she had no idea how easy it was to get fentanyl – and how cheaply, too.

Jenny Hansen noticed a pattern in her son’s behavior. Cycles of apparent calm, then drug use, and a big emotional explosion. There would be a confrontation, and then Elias would detox.

“Then finally, we knew he couldn't stop,” Jenny Hansen says. “That was the point at which we were like, okay, he's not going to be able to do this on his own.”

His parents found very little help available for teenagers with substance use disorders.

They took him to rehab at Sundown M Ranch in Yakima. But Elias manipulated his way out of it. He ended up back at home, and tried to get sober on his own – one of many unsuccessful attempts.

“I had coworkers telling me that I just needed to kick him out and had people saying, ‘Oh, you know, you just need to let him hit rock bottom,’” Jenny Hansen says. “It's really easy to say that when your child is smoking marijuana or drinking, but when children are literally dying from smoking fentanyl, you can't let them go. You have to hold on even tighter.”

In her mind, “sometimes love is ferocious,” she says.

Eventually, Elias’s parents took him back to rehab. This time he stayed all 45 days. His parents say their insurance covered most of it and they were able to make up the gap because they’ve both been working during the pandemic.

“When I got out of rehab, I stepped outside of the treatment center, and my mom got out of the car. She gave me this hug and she just like looked at me and started crying. She was like, ‘You look happy’. Like, ‘You look like a human again.”

Recovery is rarely smooth though. Relapses are part of the process and Elias relapsed too around three months after rehab.

“I'm really afraid. I'm always afraid,” Jenny Hansen says. “I'm always waiting for the other shoe to drop.”

Now Elias is on a monthly opioid blocker injection called Vivitrol. That means he can’t get high from fentanyl if he tried. He also goes to Alcoholics Anonymous -- and loves it.

“It’s the most helpful thing that’s ever happened to me in my life,” he says.

Elias wants other young people to know it’s not just old people. His parents take his recovery moment by moment. Elias feels guilty for what he put his parents through. And now he’s proud of his progress.

A month after he stopped smoking fentanyl he would wake up and think, “I have to go to work” instead of “How am I going to get money?” or “Why am I still alive?”

As time has gone on, he’s gotten more into Christianity, he says, and now he sends up prayers of thanks each morning.

There is a lot to be thankful for, he says. For one, it’s a good feeling to look his mother in the eyes and know he’s not hiding anything.