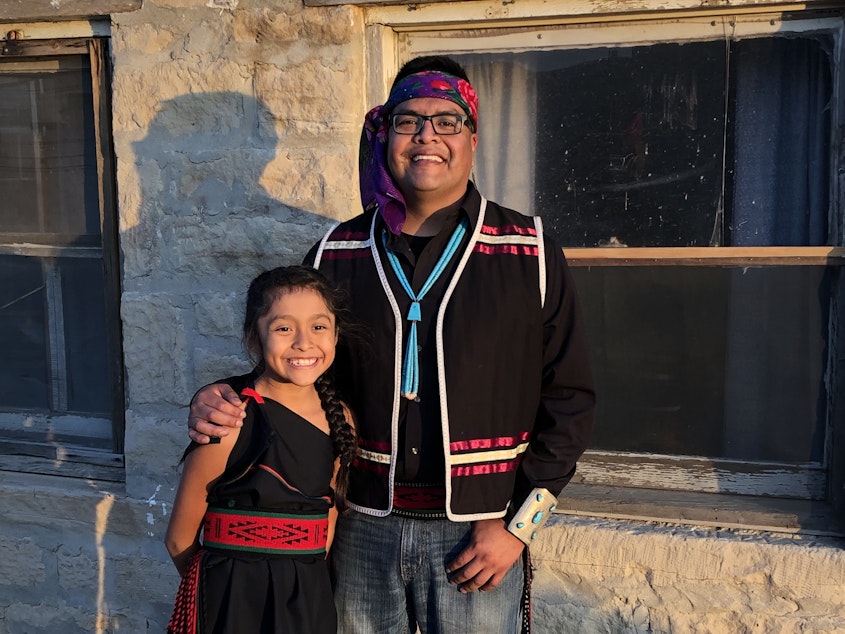

A Hopi Artist Grapples With His Complicated Legacy And Learns To Be A Better Father

Growing up in Albuquerque Duane Koyawena loved to draw.

"I did a lot of pieces that a lot of people always wanted," he says. "Like, 'can I have that? Can I have that?' Even my art teachers would ask me if they could keep stuff."

But he didn't see himself as a burgeoning artist. He only saw his father Lloyd Koyawena's talent.

Sometimes when Duane practiced drawing, he'd ask his dad to help him. He'd watch as his father pulled out his sketchbook and drew a curved line that became a tail and then the horse's mane.

"Just kinda puzzled, like, 'What is he doing?' " Duane says. "After some time, it kinda just gets put together and it's like, 'Oh, wow, ok.' "

Sponsored

Lloyd's art, which he primarily created for himself and his family, often reflected themes from Hopi culture. The family traveled from their home in Albuquerque to visit the Hopi reservation in northern Arizona to attend dances and ceremonies as much as they could.

Duane inherited more than his dad's artistic talents. Throughout his life he struggled to hold onto the good and let go of the bad.

Duane grew up the youngest of three kids as an Airforce brat. The family lived on the base in Albuquerque where both parents were stationed. His dad is Hopi. His mother is both Hopi and Tewa. Hopi is a small reservation in northern Arizona surrounded by Navajo land. Tewa is just across the border near the Rio Grande in New Mexico.

In elementary school, Duane loved to show off his dad's drawings. Lloyd coached his Little League team and taught his son to fish and to bowl.

It wasn't until Duane was 15 or so that he realized his dad had a drinking problem. He'd come home from high school, his mom still at work, to find Lloyd in the bathroom.

Sponsored

"Then discovering that he's asleep in there, "Duane says, "on the toilet."

He'd clean up his father and help him to the bedroom.

While Duane was a teenager, he was hanging out at his best friend's house when the two of them found a bottle of gin. They took swigs, passing it back and forth until they threw up. Even though he got sick, Duane says he liked it.

"I guess in that feeling, I felt that zing of like, you know, 'this is it,' " he says. "I didn't shake that. I didn't shake that part of me."

After graduating from high school he moved to Flagstaff, a small town about an hour from the Grand Canyon. Not long after Duane arrived, the police arrested him for drinking and driving. At first, he was terrified.

Sponsored

"Got work furlough, did 10 days, and I had a fine," Duane says. But then his view changed. "It was kind of like a slap on the wrist. After I realized I was like, 'Oh, man, it's not that bad.' "

So he kept drinking and driving. Within a few months, he got a second DUI, this one a felony. Then a third.

By this point, Duane would sell a drawing or two once in a while but only if he was short on rent money.

He stayed in touch with his dad, whose drinking also had gotten worse.

Once when Duane was in his 20s, he and his sister, Holly Figaroa, had to track down their father, after Lloyd had gone on a drinking spree. It took them a while to find him.When they finally did, their father was a mess. He hadn't showered in days.

Sponsored

"A lot of emotions hit and I fell into a little panic, you know, seeing my father that way and, kinda like losing him in a sense," Duane says.

In 2006, Duane's dad died of cirrhosis of the liver. He was 60.

Duane, himself, continued to spiral. After a fourth DUI, he was facing prison. His sister saw Duane going down a familiar path.

"After all of the times of, you know, going out and getting him when he was intoxicated or having my children be afraid of him," Figaroa says.

So, she got her brother into rehab in Tucson. He stayed for almost a year. While he was there in 2009, Duane's girlfriend at the time told him he was going to be a father.

Sponsored

"Of course, I was very frightened," Duane says. "You know I'm still trying to fix myself and put myself together."

But when he held his daughter, Peyton, for the first time, he made a promise to her and to himself to stay sober.

It's a promise and a practice he's kept for 12 years now.

During rehab and the years that followed, Duane's art began to reflect Hopi themes and culture, similar to his father's drawings from years earlier.

Today at his home in Flagstaff he paints skateboards and shoes, as well as on canvas. His latest show of skateboards from Native artists is called "Pivot." He curated it along with Navajo tattoo artist Landis Bahe. Duane says the title "Pivot" is about culture, evolution, art, inspiring the young, and opening the eyes of an older generation.

Sometimes when he looks at his daughter, Peyton, Duane thinks of his own father.

"He would be so mind blown," he says. "Seeing my daughter really taking to art the way she does now. I just know that he would think she would be so cool because she's just like me."

On a recent afternoon Peyton, now 12, finds her dad drawing and sits down next to him to watch.

"Dad, what are you drawing?" she asks.

"I'm drawing a taawa," Duane says.

Taawa is the Hopi word for sun.

"It looks hard," Peyton says.

"Mmm kind of is. After a while you kinda get better at it. The more practice you put in the better it gets," Duane says. "So remember you gotta practice to get better."

This story comes from the podcast 2 Lives, hosted and produced by Laurel Morales. [Copyright 2021 NPR]