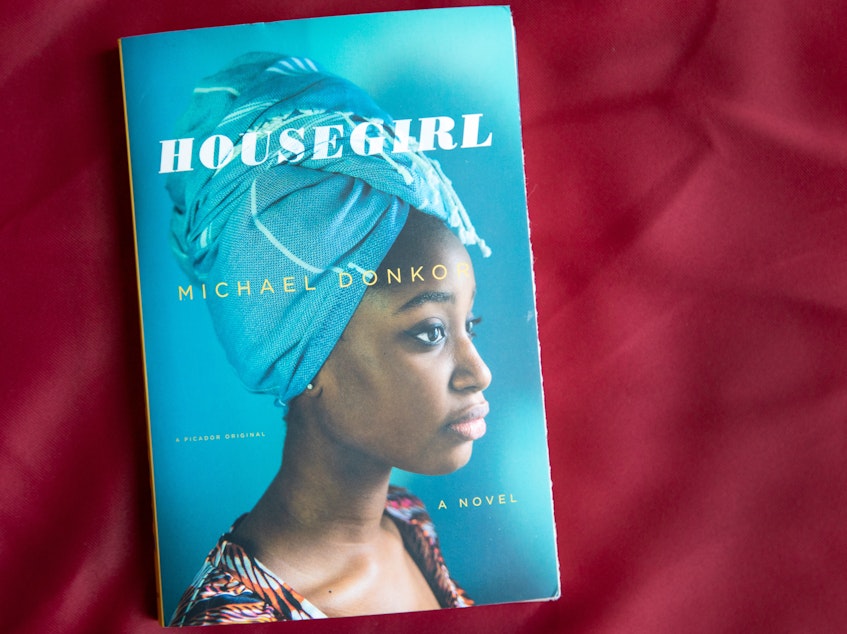

A Ghanaian 'Housegirl' Navigates A Complex Maze Of Culture And Class

When you open the new novel Housegirl, you'll find a glossary on the first pages — dozens of words and phrases in Twi, a Ghanaian dialect. Author Michael Donkor was born in London to Ghanaian parents and the glossary hints at the push and pull between two worlds.

Take, for example, the term for second-hand clothes: "Oburoni wawu literally means 'the white man is dead,' " Donkor explains. "The idea is that when the white man dies, his family sends over his second-hand clothes to Africa, to be sold in the market."

Or the word for foreigners — abrokyriefoɔ — "is a word that's thrown at me and my family, when we come over to Ghana," Donkor says, "as a clear marker that we are different from Ghanaians that live in Ghana."

The two teenage girls at the center of Donkor's debut novel are trying to find their place between these two cultures. Amma is growing up in London to Ghanaian parents. When we meet her, a gap has opened up between the once-outgoing girl and her family.

The parents hire a "house girl" named Belinda, who leaves Ghana to come live with them — but Belinda's job is not to clean or cook. In exchange for an education, she's asked to befriend Amma. "You get this uncomfortable clash of upbringings," Donkor says, as Belinda enters Amma's privileged world.

Interview Highlights

On Belinda's job — which is more than simply drawing Amma "out of her shell"

Labor in the novel takes on many different forms. ... I think Belinda's real task that she's given by Nana and Doctor Otuo — the parents of Amma — is that she is meant to kind of teach Amma how to be a proper Ghanaian woman ... a woman who is submissive and obedient and quiet and conforms, essentially. And when Belinda meets Amma, she's not doing any of things at all. She's being kind of sullen and rebellious and Nana and Doctor are really concerned as to why that's the case. So that's really what Belinda's job is in London — it's to kind of tame Amma, I suppose, and also maybe to try and find out why she's suddenly changed the way she's behaving.

On grappling with certain aspects of Ghanaian culture

I think there's a kind of traditionalism which lots of people kind of talk about in the vein of wanting to preserve culture, and wanting to not lose a sense of the great rights and rituals that have been going on in various parts of Ghana for centuries. But there's also a kind of repressive aspect to that traditionalism as well. ... People who feel that they don't necessarily conform to the kind of expected behaviors or identities of Ghanaian people feel quite trapped. ... Some of the young people who don't fit the mold, as it were, find themselves in terrible positions and find themselves deeply troubled and fractured by being pulled between this desire to fit in with the culture around them and the desire to be true to themselves.

On the book beginning and ending with a funeral

The loop idea — I think it came from my sense that I wanted to think about progression and movement. ... This is a novel in lots of ways that feels like it's about moving forward. Belinda moves from the village to the city and then she moves from the city to the UK. But then there's always a kind of longing to go back. And so I'm sort of thinking in the shape of the novel about the idea of looping and returning and going back and I suppose the idea of home. ... We can't really escape from ... where we've come from. ... We can sort of move on in all sorts of ways, but there will always be a kind of core of us that's sort of deeply related to that place that we sprang from.

Melissa Gray and Connor Donevan produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Beth Novey adapted it for the Web. [Copyright 2018 NPR]