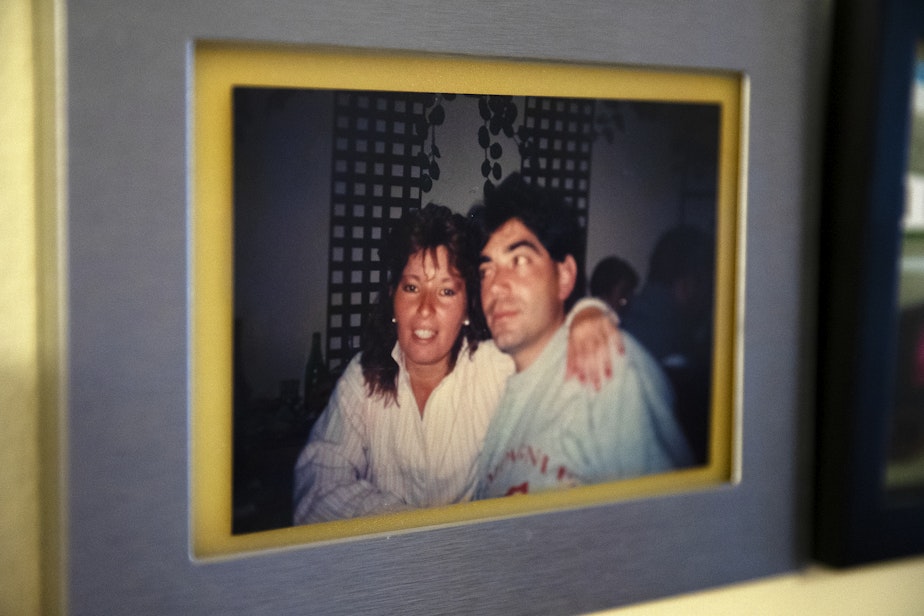

'You’re my queen.' A Latina wife with dementia and the loving husband who cares for her

A

t an apartment complex just off Highway 99 in Everett, 66-year-old Omar lives with his wife Marta. In their apartment’s living space, there’s a print of Jesus’ last supper on the wall, and on a recent September afternoon, there was a muted soccer game on the television. Marta was in the bedroom, taking her afternoon nap.

“You’re my queen, isn’t that right?” Omar asked Marta as he woke her up. “Aren’t you the queen of the house?”

“No,” Marta answered — but she smiled.

KUOW agreed not to publish Omar and Marta’s last name because they’re undocumented.

They’re originally from Argentina. When they moved here in the late 1990s, they started a small cleaning business, to make the money they lived on until the mid-2010s, when Marta started to get sick.

Lea esta historia en español: 'Eres mi reina.' Una paciente que sufre de demencia y su amoroso esposo enfermero

“She started forgetting so many things,” Omar said. “She became a little aggressive.”

Omar said she would sometimes get angry — for no apparent reason — and she even left scratches on his arms.

About five or six years ago, Omar stopped working and became Marta’s full-time caregiver. He was able to do this with the support of his adult son.

Omar and Marta’s situation is common within Latino communities, in which relatives often become caregivers to sick family members. Such a scenario is on track to become even more prevalent, with the U.S. population of Latino seniors expected to more than double over the next 20 years, and with Latinos being one of the groups most at risk of developing dementia.

In Washington state, services for those family caregivers aren’t keeping pace with the growing need.

These days, Omar does everything for Marta: He feeds her, changes her adult diaper, and gets her in and out of bed. He had a seat installed in their shower, so she can sit while he bathes her.

“It’s hard work,” he said. “You have to have patience, and some strength.”

But Omar said he wants to do this, because he wasn’t able to take care of his own mother when she was diagnosed with Parkinson’s after he’d moved to the U.S. Because he was undocumented, he couldn’t go back to see her or help out.

“The only thing I could do was send money,” Omar said. “So it’s like all the care I wasn’t able to give my mom — I’m giving that to Marta.”

Experts don’t fully understand why Latinos, along with Black people, are at a heightened risk of developing dementia, but they point out these two groups are more likely to have risk factors like living in poverty, or suffering from diabetes or cardiovascular disease.

On top of that, the number of older Latinos in the U.S. is rapidly increasing.

“The aging of the immigrant wave that came in the 1980s, that’s going to be a large number of people,” said Leo Morales, a physician and the co-director of the University of Washington’s Center for Latino Health. “And it’s their second-generation children that are going to be facing this — the wave of aging adults; they’re going to be taking care of them.”

Morales, who is also UW Medicine’s assistant dean of health care equity, said Latinos tend to avoid bringing paid caregivers into the home, or sending their loved ones to a memory care facility.

“Culturally, there’s the expectation that children will take care of the parents,” Morales said. “I think disproportionately it falls to the women in the family.”

Morales said to help ease the situation, more bilingual, bicultural social workers are needed, who can help families feel comfortable using outside services.

Janette García is one such social worker. She often helps family caregivers explore their options in her work at Seattle’s South Park Senior Center.

García said people come from all over South King County, and even from Tacoma to talk to her, because there are so few Spanish-speaking social workers in the area.

She said there are some free resources available to family caregivers, regardless of their immigration status. A big one is 20 hours of free, in-home care every month, so caregivers can take a break for a few hours. The problem is that there are so few home care workers available that some families spend months or years waiting for this in-home care.

RELATED: A wheelchair ramp, respite care: What WA's long-term care tax could realistically get you

There are also free meals and house-cleaning — and in King County, six free therapy sessions for family caregivers, though finding a Spanish-speaking therapist can be difficult.

“People don’t know about these resources,” García said, “even though they’re not enough.”

One thing that’s needed, she said, are Spanish-language support groups. The Alzheimer’s Association, for example, has about 75 support groups for caregivers statewide — but none are in Spanish. Employees from the Association said the caregiver support groups are run by volunteers, and they’re looking for Spanish speakers.

Back in Everett, Omar is one of the lucky few who has managed to get some free in-home care for Marta through Snohomish County. A home care worker comes on Sunday afternoons, so Omar and his son can go out for a few hours.

“A couple of weeks ago, we went to Seattle to go for a walk,” Omar said. “Sometimes we go to a sports game nearby, or to the casino.”

Omar said he needs that time off: a few hours to disconnect from Marta’s needs, clear his head, and come back home with more energy and more patience.