What these women couldn’t say publicly about Sherman Alexie until now

Several women who have accused author Sherman Alexie of sexual harassment have now gone public with their stories.

As this story unfolds, it’s stirring some tough conversations within literary and Native American communities in the Northwest.

In Alexie’s adopted hometown of Seattle, the whisper network around him existed for years. Women writers told each other about inappropriate behavior or unwanted advances.

One who’s now come forward publicly is Elissa Washuta, a writer and member of Washington’s Cowlitz Indian Tribe.

“The silence was really destructive to me,” Washuta told KUOW. “It was destructive to my health. I was fearful for my career and it was just getting to be so difficult to not be able to say anything.”

Sponsored

Washuta is one of three women who accused Alexie of unwanted sexual advances in an NPR story this week. According to NPR, several more women also recounted off-the-record stories suggesting Alexie used his power and celebrity to try to seduce them -- women who felt they needed his favor to be recognized in a challenging literary environment.

“Sherman Alexie's work and voice and approach seemed to be considered somewhat of the gold standard and we are all considered sort of in relation to him in a certain way,” Washuta said.

Early in her career, Washuta said, Alexie told her he could have sex with her if he wanted. Another time at a conference they were both attending, he sent her photos of a hotel room bed with condoms on a nearby table.

“I don't want any young woman to be in that position that I was in ever again with Sherman Alexie where you know I was sitting in a bar and he was telling me that he could have sex with me and that I just had to endure [hearing] it and not make any waves because it felt that important for my career,” Washuta said.

She places some blame on a publishing industry that she says put Alexie on a pedestal and enabled him to act as sort of a gatekeeper for other Native writers.

Sponsored

“Publishers and agents and book critics can all look at this and see that for so long one writer has had a disproportionate amount of their attention to the exclusion of other native writers,” she said.

Alexie did not reply to numerous requests for comment. But he did recently issue a statement of apology, saying some women were telling the truth about him.

"I have done things that have harmed other people, including those I love most deeply," Alexie said in the statement. "To those whom I have hurt, I genuinely apologize. I am so sorry."

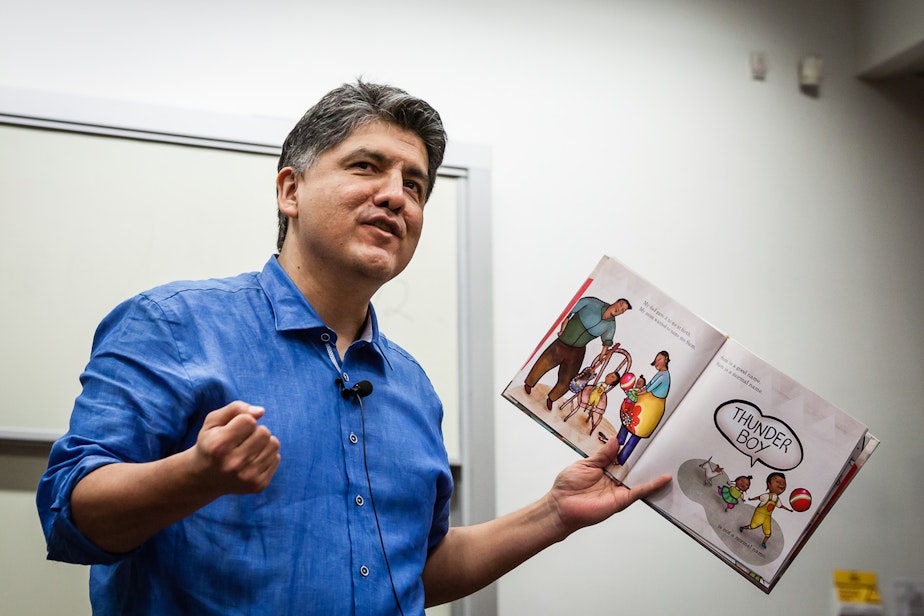

Alexie grew up on the Spokane Indian reservation and his work centers on native life and struggles.

He’s an icon, a celebrated “success story” within the broader Native American community, where many are now grappling with these allegations.

Sponsored

“It's also going to take us to really ask the uncomfortable questions,” said Calina Lawrence, a 25-year-old artist and member of the Suquamish Tribe. She’s also an activist who speaks out about violence against women.

One issue Lawrence wants raised in her community is Native Americans’ role in elevating powerful voices and how to hold those voices accountable.

“I think it's really difficult because we're just so eager to have representation that sometimes we're willing to sacrifice the imperfections just so that we're at least seen and heard,” Lawrence said.

She is optimistic that her generation is ready to confront some of the #metoo issues in Indian country. And a silence that’s spanned generations.

“It's a big huge 10-foot wave that we're standing and looking at,” she said.

Sponsored

Writer Sara Marie Ortiz is a member of the Acoma Puebla tribe and a longtime family friend of Alexie’s.

She calls the allegations against him “immensely complicated.”

In her view, the #metoo movement has created a blueprint that doesn’t fit Native traditions or culture.

“We have a responsibility to create our own model,” Ortiz said. “We have old systems of restorative justice and different processes that have nothing to do with social media and have nothing to do with the often punitive, often repressive and dehumanizing thing that happens in courtrooms and in the court of public opinion in the U.S.”

She also sees this moment as an opportunity for others, and for herself.

Sponsored

“I don’t want to underestimate my own agency or voice or power as a native woman, calling upon our native men but our men in general to just be better and to be more vulnerable and their best selves,” she said. “And just more and more honest than ever before. Because that is what it’s going to take.”

And Ortiz is glad more women are coming forward to tell their stories. And more men, to listen.