We asked our listeners about racial microaggressions. The responses proved the point

On the night of Dr. Roberto Montenegro’s dissertation defense celebration, he went out to dinner at a fancy restaurant with his wife and colleagues. He felt like he was on top of the world at the end of the night.

Until, as he stood in line waiting to claim his car from the valet stand, a woman walked up and handed him her keys. She assumed that because he was Latino, he was there to park her car.

“I vividly remember turning red,” Montenegro told Bill Radke in an interview. “I don’t often turn red. I remember my heart pounding. I remember feeling really confused and hurt and angry.”

Montenegro didn’t say anything. Then it happened again moments later with a different diner.

“It was just a reminder of being different and being categorized — and almost not belonging in that setting,” he said.

Sponsored

Montenegro researches the effect that kind of racial microtrauma — commonly called microaggressions — has on a person’s physiology and health. He sat down twice with Radke this month to talk about his research and to offer some advice for those on both sides of these damaging remarks and actions.

Montenegro said his research is still in early stages, especially as it relates to how microtraumas impact children. But his goal is to map how consistent stress from small, traumatic events changes the body’s cells and effects serotonin reuptake receptors, which are associated with symptoms of anxiety and depression.

“The repeated experience of being alienated, being dismissed, being invalidated — those take a toll and is believed to have a great impact on the mental health and the biological health and the overall well-being of people,” Montenegro said.

Related: Seattle author Ijeoma Oluo explains how she is "drowning in whiteness"

Sponsored

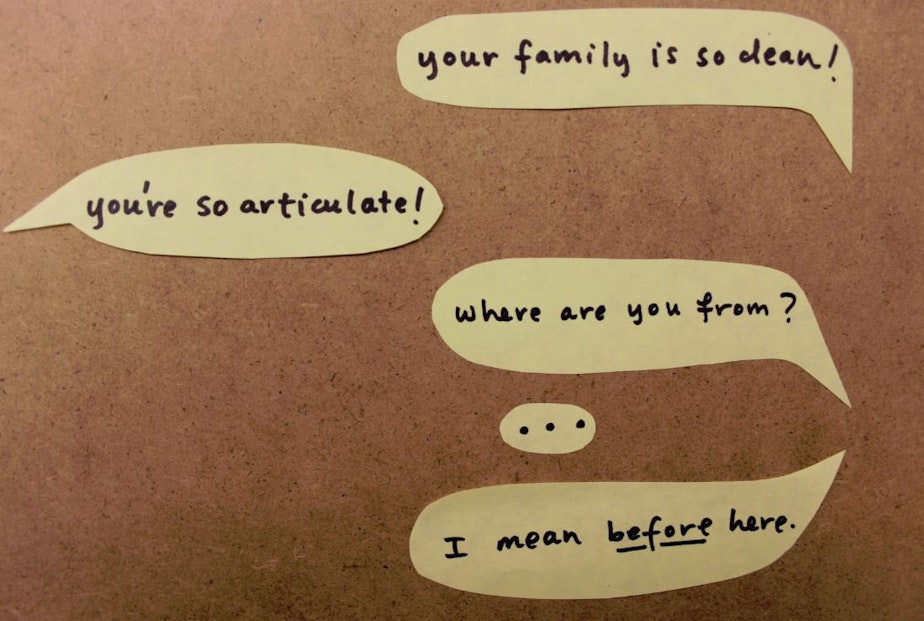

Microtraumas or microaggressions are a common source of stress for racial, sexual or gender minorities. We asked the KUOW Facebook community to share what microaggressions look like in their lives, and here’s a sample of what we heard.

Everett wrote: “When I'm the only black person in a business meeting, and after the meeting, someone says, ‘You're so well spoken’—what do you expect from someone in my position? I bet they didn't tell the other white people in the meeting that they're well spoken.”

Vic commented: “White people automatically trying to talk to me in Spanish. I’m American as hell. You don’t sound educated and empathetic, you show me you live on assumptions.”

And Emily added: “In a team building meeting, someone asked me if my personality traits were somehow related to the color of my skin. The worst part was that when she asked the question, stumbling on her words, she paused and pointed to her skin. I was caught off guard and embarrassed, but mostly for her.”

Montenegro said white people often react defensively or dismissively when confronted about racist microaggressions, and the conversation on Facebook illustrated that. In response to Everett’s concern, Elizabeth wrote:

Sponsored

“I think that interpreting it as aggression is misguided and ‘thank you’ is a way to handle any ‘compliment’ whether you like the statement or not … I am white and get compliments on my communications styles all the time. I think there are bigger things to concern ourselves with than people's off-base, yet sincere compliments. Geesh.”

Everett responded: “You're right, there are bigger things, but that doesn't excuse the fact that white people shouldn't be shocked that a black person can speak professionally.”

But Montenegro said that microaggressions can be a big thing — and they might be especially traumatic for children. He said he works with transgender children who struggle to know what to do when they are persistently misgendered.

“The way that we are encouraging these kids to address this is, you can’t control what other people say to a certain extent, especially in children,” he said. “You can control your thoughts and you can control the distortions you have that are being fueled by a lot of the hurt and the trauma you’ve experienced.”

But he said adults might sometimes benefit from confronting the offender.

Sponsored

“The first thing to ask is, is it worth it?” Montenegro said. “Is confronting the person really worth it — personally, professionally?”

If the answer is yes, he recommends broaching the topic in a safe environment where the person will be more open to engaging and being educated.

“It sort of challenges your idea of being this good person, this politically correct person, this progressive person,” Montenegro said.

He said he uses the word “microtraumas” instead of “microaggressions” because he’s found people respond more receptively.

“I am taking care of your fragility,” Montenegro told Radke. “It’s exhausting, Bill.”

Sponsored

But Montenegro added one caveat: “I don’t want to place the onus of dealing with these kinds of discriminatory behaviors on the recipient.”

So, what if you’re the person who committed the microaggression?

Montenegro said fighting defensiveness is key, as is acknowledging that you messed up.

“It’s about having the humility of being open to feedback when some actually approaches you,” he said. ”... Being okay with being challenged and being okay knowing that you will either aggress or be the aggressor at some point, and that you will fluctuate is very important.”

Maybe Montenegro’s most important takeaway would be this: “Microaggressions are not about getting your feelings hurt. It’s about the accumulation of these continuous invalidations, alienations ... They build up and they continue to cause difficulties.”

Produced for the web by Amy Rolph.