Remember the Native occupation in Magnolia in 1970?

People across the nation are protesting and Native Americans are occupying. It’s against the Dakota Access pipeline near the Standing Rock Sioux reservation in North Dakota.

Members of the Standing Rock Sioux are worried the pipeline could harm drinking water and damage sacred sites.

Seattle got involved in the protests this week, but protests and occupation over Native American land rights isn’t new to the city.

Let’s get a historical perspective of a Native occupation that happened in Seattle 46 years ago.

Randy Lewis of the Colville Indian Reservation lives in Seattle: “I was one of the troops I was one of the warriors.”

Sponsored

Lewis was involved in the occupation of Fort Lawton at Seattle’s Discovery Park in 1970.

It happened the year after the occupation of Alcatraz Island in San Francisco.

Lewis says it all stemmed out of the Civil Rights movement.

“There was this feeling amongst American Indians slash native people that we had we had systematically been pushed and killed from the East Coast to the west coast taking everything away from us.”

Urban Indians wanted to start reclaiming lands that were being slated for surplus and turn them into cultural centers.

Sponsored

Back in 1970 Fort Lawton was being declared as federal surplus. In other words, the federal government had the land but didn’t need it anymore, so they were looking to give it up.

The Native American community wanted it, and Seattle wanted to buy it to build a park.

The city and native community both thought they had rights to the land. And when it was looking like the city was going to end up with the land, the native community occupied.

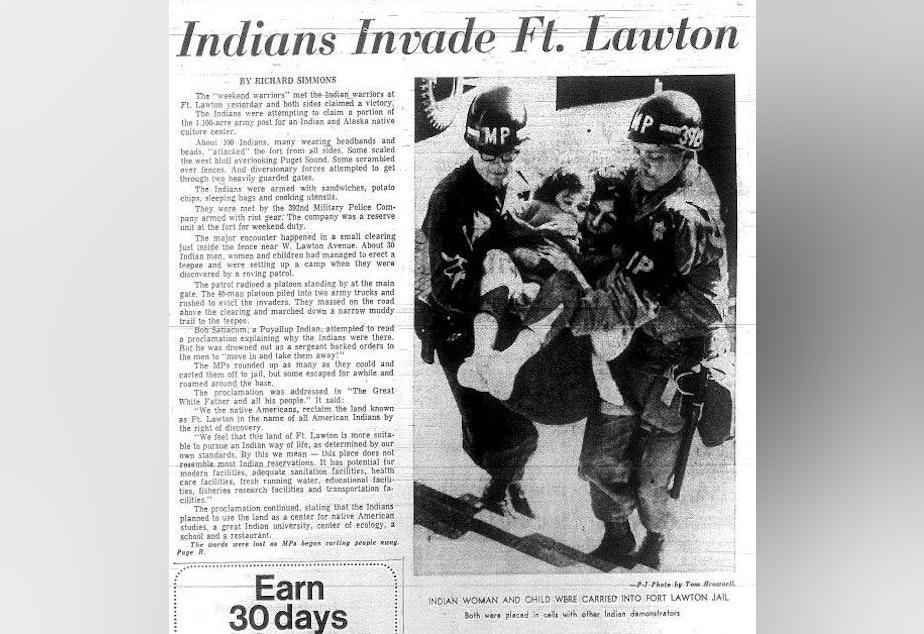

When 100 people from tribes across the region came in to occupy Fort Lawton, they were greeted by military police.

And much like Standing Rock right now, we were swimming in a sea of military.

Sponsored

And Lewis says the Natives were beaten.

"People were hospitalized from this. There were some injuries and as they rounded us up, they took us over to the stockades. Two cells, 100 people in two cells. Literally you couldn't fall down."

They were eventually released.

The military surrounded the fort with barbed wire, but Lewis says, the Natives found a way around it.

"We scaled the cliff Magnolia bluff when the tide was out. We came up the bluff carrying everything that we needed – teepees, teepee poles and hid under the roots of the Madrona trees on the bluff."

Sponsored

Eventually the fight went to the courts and the Native community was able to claim 20 acres of what is now the more than 500-acre Discovery Park. The Natives did end up getting what they wanted: A cultural center. Today, the Daybreak Star Indian Cultural Center in Discovery Park includes a preschool, elders program and art program among other things.

But Lewis sees what’s happening at Standing Rock as the last battle.

"In many ways Standing Rock is again a reminder of what our dreams were. Standing Rock is basically the last stand."

Lewis says Standing Rock has become a much bigger movement than Fort Lawton, but both occupations brought people from many tribes together.

"It's become the uniting factor for all Native Americans. We're no longer viewing ourselves as bands and as tribes, but an Indian nation."

Sponsored

The White House said yesterday they are looking to gather more input from Native people as officials contemplate projects like the Dakota Access Pipeline.

This comes the same week the Army Core of Engineers delayed a key decision on whether construction on the pipeline can go ahead.

That likely won't be decided on until early next year.