Tacoma approaches affordable housing from a new angle: anti-displacement

As cities throughout the Seattle area grapple with the dire need for more and affordable housing, Tacoma is attempting to come at the issue from another angle — anti-displacement.

“As a kid who grew up in Tacoma, I tell people that I got to live in every neighborhood, because there was something affordable in every neighborhood. We want to make sure that we’re building that same Tacoma," Mayor Victoria Woodards told Soundside.

“Density is coming, but we as a city have to be responsible for where we allow that density to happen. It has to happen in places that make sense."

The Tacoma City Council approved an anti-displacement plan in early February. It's an extension of the city's affordable housing strategy that was passed in 2018. While these strategies address overlapping issues, and utilize similar tactics, they are viewed as different approaches. Affordable housing deals with the creation of more units as the city evolves. Anti-displacement is designed to preserve what Tacoma already has — its residents and their homes. If successful, it would counter factors that force residents to ditch Tacoma. Woodard also notes that the anti-displacement plan is expected to change and adapt moving forward.

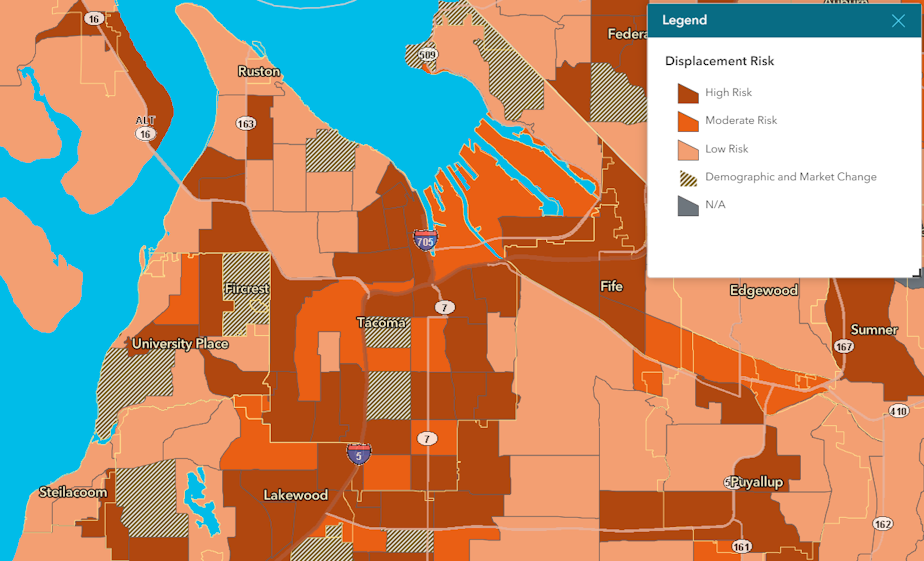

The anti-displacement approach is also viewed as a means of mitigating other issues, such as the lingering effects of Tacoma's past redlining policies. The plan references the Washington State Department of Commerce's Displacement Risk Map (currently in draft form), which highlights areas where residents face higher risk of being displaced. Notably, areas with a higher percentage of residents of color, and low-income households, are more likely at risk. One such area is Tacoma's Hilltop neighborhood, which the plan specifically points out, along with downtown, South Tacoma, and East Tacoma.

Tacoma's anti-displacement plan

The plan has 21 points spread across a handful of focus areas, such as preserving and rehabilitating existing affordable housing. Tenant protections are included. The plan also includes homeownership and down-payment assistance for first-time homebuyers entering the market, and promotes mixed-income developments.

There are also strategies that may sound familiar to other cities, such as streamlining the permitting and development process at city hall. Seattle nixed its design review process for affordable housing in 2022. The idea is to remove delays and lower costs for this form of housing.

Tacoma's anti-displacement plan also opens up potential for accessory dwelling units (referred to as an ADU or DADU). These are commonly referred to as "mother-in-law apartments," or "backyard cottages."

Seattle previously established an ADU plan that provides 10 ready-to-go plans for backyard units. The plans fast-track the permitting process. Between 2019 and 2023, Seattle issued 1,000 permits for such ADU projects. In 2022, 427 ADUs were approved for units attached to a home (such as a garage conversion), and 551 detached units (like backyard cottages); a third of these were on single-family properties, and 11% were ultimately used as Airbnbs.

Part of Tacoma's philosophy around anti-displacement is a wariness for how improvements to an area can raise the cost of living for residents in that area. It also attempts to balance types of housing with increased density. This debate often happens around single-family zoning in cities.

“When you make improvements to neighborhoods, that drives up the cost of housing," Woodards said. "But every neighborhood deserves to have light rail, to have new schools, or remodeled schools. Everybody deserves to have great things in their neighborhoods, but we know what happens when we do that.

RELATED: Backyard cottages take off in Seattle. But who benefits?

"In the middle of a single-family home neighborhood, it doesn’t make sense for a 200-apartment-size building, but on a corridor where there is transportation, where there are services, it makes sense to do that there," Woodard said. "But you could, in a single-family neighborhood, do a duplex."

Many of these housing tactics come nearly a year after state lawmakers passed a suite of reforms that opened up more types of housing developments.

"What we’re doing," Woodard said, "is putting density where density makes sense, not just putting it everywhere for the sake of having more housing, but to continue to create communities that make sense, where neighbors feel welcome and get the services they need. Not everybody wants to live in a single-family home and take care of a yard and all of those things. So we want to make sure we have different types of housing for people who want to live in Tacoma, and who work in Tacoma.”