Twitter Lessons From The Boston Marathon Bombings

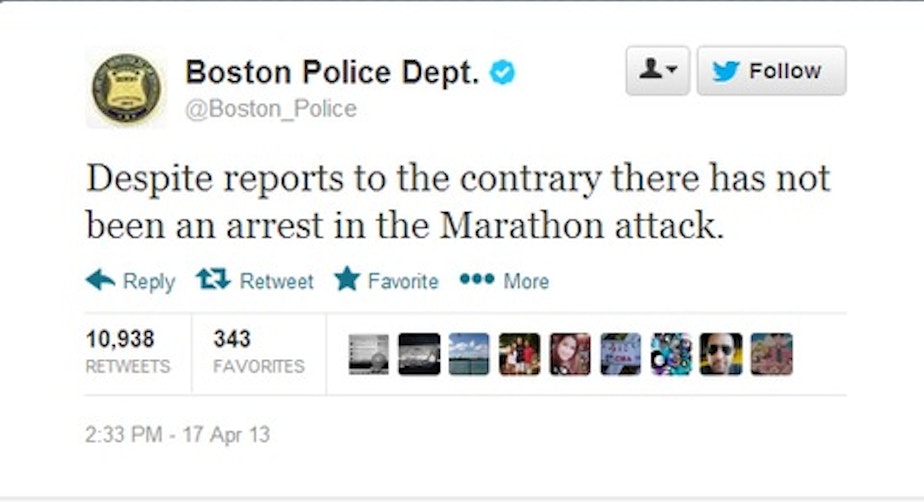

When the deadly Boston Marathon bombings happened a year ago, people flocked to social media sites like Twitter for information. But that led to some problems, including the misidentification of one of the suspected bombers and other reports that turned out to be false.

Some local researchers at the University of Washington and Northwest University in Kirkland have been studying the thousands and thousands of tweets that went out after the bombings.

Kate Starbird, an assistant professor in the UW’s department of human centered design and engineering, was a part of the research team. She spoke with KUOW’s Jamala Henderson about how misinformation went viral on Twitter during the Boston Marathon bombings.

The research has helped them come up with ideas on how to flag inaccurate information on Twitter.

One issue the team studied was “crowd correcting”: when bad information goes out, the crowd will right it. Starbird said their research didn’t entirely disprove this theory, but the correcting system is flawed.

“The crowd corrects bad information it says with, ‘Oh wait a minute, that rumor’s not true,’” Starbird said. “This happens at such a low volume, the signal of the misinformation or the misinformation itself spreads much further than the correction.”

Starbird found crowd correcting problematic because the same misinformation may resurface, and it wouldn’t be corrected later because people were focused on something else. In that case, more people would see the misinformation than the corrected information.

Starbird said one of their goals is to automatically detect misinformation, which she said was a difficult problem computationally.

“It turns out to be really hard to train computers to make sense of textual language, especially tweets, having to do with the fact that there’s just not a lot of words there,” Starbird said. “But it might be easier to train a computer to detect the corrections, because when people correct the information they do it in a pretty consistent way.”

She said if computers could be trained to spot a correction, it may be possible to amplify the correction or devise a system to signal that a tweet has questionable information in it.

Produced for the Web by Kara McDermott.