Where’d all the smoke go? It didn’t just disappear

Recent rains have washed away the thick wildfire smoke that fouled Washington’s air for much of September.

That smoke didn’t just disappear, though -- where did it go?

Some smoke blew elsewhere. But eventually, the ash and soot that turned the sun into a pale sickly orb along the West Coast comes down to earth somewhere.

Wildfire smoke is mostly water vapor and other gases, including carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide. It’s also made of tiny particles of soot that can contain metals and long-lasting carcinogens like PAHs (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons).

Smoke on the vineyard: NW wine industry worries about possible smoke taint

Once a good rain knocks those fine particulates out of the sky, they wind up on the ground and in the water.

Stream ecologist Markus Von Prause with the Washington Department of Ecology said streams can be overwhelmed with a pulse of pollution when the first big rains hit after a wildfire.

“It’s like sending a biological system into complete shock,” Von Prause said. “You’re just basically taking a lot of contaminants and moving them all at once.”

That shock can come from various sources, and it can be hard to separate out where the water pollution actually comes from.

But scientists say the biggest problem isn’t the smoke. In burned areas, it’s all the soil that erodes from slopes denuded by fire.

“We’ve seen millions of acres being burned,” Von Prause said of Washington’s wildfires in the past five years. “When you have that much vegetation removed from millions of acres, it affects the stability of your watershed.”

Erosion can muddy fresh waters and harm the ability of aquatic creatures to breathe and grow.

“When you have a blanket of sediment, your photosynthetic rates are reduced highly,” Von Prause said.

University of Washington environmental health scientist Edmund Seto said the PAHs in wildfire smoke were his main concern.

“They’re a whole class of chemical compounds, and quite a few of them are cancer causing,” he said.

Seto said PAHs are ubiquitous, generated “whenever you burn anything, whether it’s fuel in your car, or you’re doing a barbecue or you’re eating smoked meats.”

He said the chemicals in smoke can wind up in water, in soil and in crops.

“We don’t know how much is going to get distributed in these different pathways that eventually could loop back around [and] affect humans,” Seto said.

Globally, it’s estimated that about one-sixth of PAHs come from wildfires.

“What makes this episode so scary is the magnitude of the fires, especially in California,” Seto said.

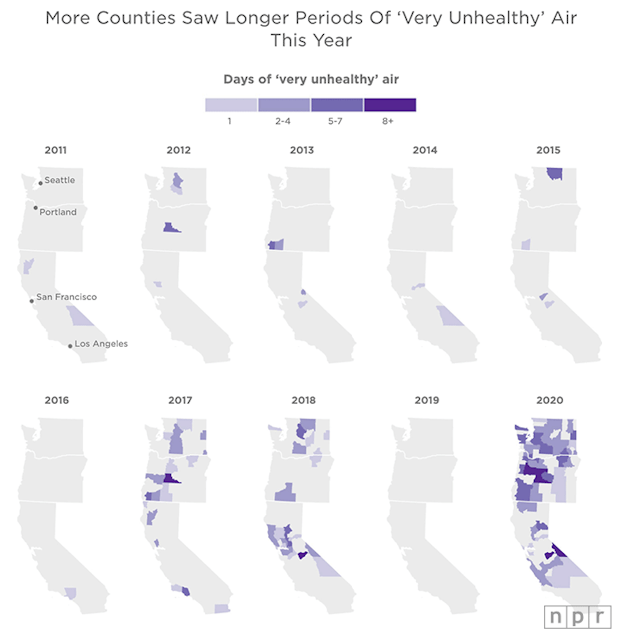

NPR found that nearly 50 million people in California, Oregon and Washington -- or 1 in 7 Americans -- live in counties that had at least one day of "unhealthy" or worse fine-particle pollution during wildfire season so far this year.

Fueled by a warmer climate that has left much of the land drier and more prone to fire, 2020 is already the worst year on record for wildfires on the West Coast.

Many counties, including Clark, Kitsap, Pierce, Snohomish and Thurston in Washington state, experienced “very unhealthy” air from wildfire smoke for the first time, according to NPR.

As for smoky particulates that fall to solid ground, University of Washington atmospheric scientist Sarah Doherty said most of them will remain in the soil rather than significantly polluting waterways.

“For sure the contribution of deposited smoke to the soil isn’t a significant environmental impact,” Doherty said in an email.

The first heavy rains after a dry Northwest summer can also send a summer’s worth of gunk like motor oil, brake linings and tire dust into streams near roadways.

That often makes October a rough month for things that live in suburban streams. Many young coho salmon die gasping for breath each fall as a summer’s worth of poison suddenly floods their creeks.

Stormwater runoff from highways and roads is the largest source of toxic chemicals in Puget Sound, according to the Puget Sound Partnership.

Seattle broke two daily records for rainfall this week (with 0.89 inches on Wednesday and 0.85 inches on Thursday), and the National Weather Service forecast for western Washington is for more rain.

Still, we’re not out of the woods, so to speak, for breathing smoke.

The fire season in California, where much of the September smoke darkening Washington skies originated, lasts until early November now.

Fire seasons throughout the West have lengthened with the earth’s warming climate, and the impacts of fire and smoke are expected to keep worsening as fossil-fuel use continues to drive the global climate into uncharted territory.