‘You’ll Never Forget This Baby’: Moving On After SIDS

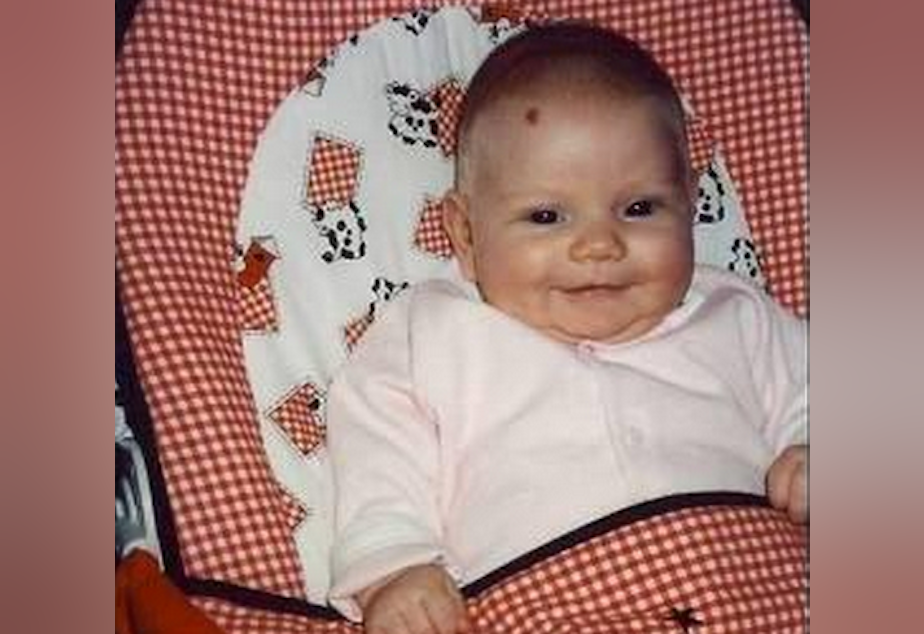

In 2001, Aileen Carrell's 3.5-month-old daughter died of SIDS at her day care. Carrell shared her story with KUOW's Kim Malcolm.

My daughter died on the first day of starting day care.

Lucy went down for an afternoon nap, but she was placed tummy down. She had never been placed tummy down. I’ve learned since that about 20 percent of infant deaths occur in day cares.

A daughter of the day-care provider went in to check on her, because she hadn't woken up, and found her dead. They did mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, and they called 911.

The first responders came and worked on her. My husband came upon the scene with the fire trucks and everything. They brought him in. One of the parents had taken my son off-site, and they had taken the kids out.

My husband came home; he assumed I was home. He was with a chaplain. When we returned to see her, they placed her in my arms and tried to explain to me. It’s a blur, but I remember holding her in my arms.

And she was gone.

I was breastfeeding, so I had to stop breastfeeding. I had to bind my breasts so that I would stop producing milk. So there was physical pain.

I was going a little nutty. I was thinking, what if she really wasn't dead? Maybe it was a fake sleep. This has to be wrong. It can't really be happening. A nightmare, literally, that you just cycle through and you can't deal with.

We had a little boy at home. And honestly if it wasn't for him, I might not be here. Because I remember saying to my sister, “If there's any medicine in the house, take them out.” I don’t want the risk that I’m going to off myself, because that’s where I feel like I was headed.

I was really dark. And there was not a lot of conversation with my husband. He was equally as inconsolable as I was. Just trying to get out of bed every day was Herculean effort.

A couple days went by, and we got our got the results back from the King County Medical Examiner – sudden infant death syndrome. And we're like, what is that?

The way they classify SIDS, or sudden infant death syndrome, is that if they can’t come up with a conclusive reason why she died, they would rule it is SIDS. I asked, was something wrong? The only thing they said is that she was placed tummy down.

She had one little ear infection but was otherwise completely healthy. She loved her older brother and could hear his voice instantly. She was really an engaged, alert, healthy baby, gaining weight, tracking things.

Trying to explain it to people, the best I could say was it was like she turned off. I was trying to explain it to my 3-year-old, who was trying to understand. We said she went to sleep, and her body just turned off.

Everything changed. I come from a big family, a supportive family, one of six kids. We were all having kids at that point. It devastated my parents. I remember my mom trying to hug me, and she said, “I don't know what to do, I feel like I'm failing. I don't know what to do for you.”

It wasn't until years later I realized she was grieving just as badly as the next person, because she also suffered the loss and then she was suffering my sadness as the mother to her own child.

My husband had a sales job that wasn’t really inspiring for him. I was working for Starbucks Coffee Company. I had a great job, which I loved. So we made the decision that I would go back to work, and he would stay home.

We said no more day care. Not that we didn’t like the day-care provider. We thought it was a great environment, but we just couldn’t be back there. No one else was going to be able to care for our children as well as us.

Going back to work ended up being a very good thing, because my work group was really supportive. They had gotten help from the local SIDS organization, who I work with now. I was doing that kind of thing as well, and then my husband and I started our own business, which has been very successful.

***

We've had two more children since then, so now I have three surviving boys. They’re 16, almost 12 and 3.

Our son came along about 18 months after Lucy died. We were panicky. We did all the research about what makes a safe sleep environment, and we were vigilant to the T.

No bed sharing. He slept on his back in a room. I had a temperature control on the bed. No crib bumpers, no fuzzy stuff in the bed. At first he was right next to our bed.

I wasn’t able to sleep terribly well when he was little. Even during a nap, I sometimes sat in the room and poked him a little bit. If I thought he had a chest cold, I’d sleep next to the crib. I did it with my son Sam as well. I would lay next to the bed and put my fingers into the crib, checking his breathing constantly, watching for the chest to move up and down.

I still do it with them now that they’re teenagers. If they sleep in a long time, I’ll see what they’re doing. If there are covers over their head, boom, the covers are pulled down.

I promote the ABCs – alone, on their back, in the crib.

A lot of people do bed sharing, and they would argue with me on that, but if you're trying to give your kid the best fighting chance, and you've had a situation like mine – this is evidence-based research that shows this is the safest ideal way. Even if we found out a clue about the inner ear research, we’d still promote the same thing.

***

I remember talking to a fellow SIDS parents early on who was trying to console me. We were talking within the first week or two, and I said, “I can’t talk to my husband. He won’t talk to me about it. I can’t talk to him about it.”

My husband was a doer; me, I wanted to figure out how to talk about it and find some answers. So we weren’t a good resource for each other in that respect.

So this really wonderful SIDS mom said to me, “Don’t let the ending of your marriage be another tragedy. You already had one.”

Once I understood that wasn’t going to happen with him, it was good, and I found other ways I can talk about my daughter.

We can’t talk about that day without one of us cutting the other off. It’s just too hard. It’s too dark. We kind of have an unwritten rule – we don’t talk about it.

***

When I work with other families, the main thing I tell them is that they’re going to make it.

“You can survive this, and you can come out of this and still have hope and still have love. You will never forget your baby.”

A lot of people worry they’re going to forget this baby. And I say, “You’ll never forget this baby. Feel free to talk about your baby if you feel like you want to talk about your baby. Because your baby really existed, and nobody has the right to tell you – just because they’re uncomfortable – that you can’t talk about your child, whether they’re with you or not.” We talk about our kids as parents.

I tell them they won’t walk it alone. There are parents like me there to help. The organization I work with, Northwest Infant Survival & SIDS Alliance, that’s our primary base function is to help families. We’re a resource, even if they don’t want to talk to us for months. They can call me in the middle of the night. Now a lot of people text, or I meet them for a cup of coffee.

One day we’re going to crack the code on this. We’re going to figure it out, and have a great day, because we don’t have to continue to spin with the why, the why, the why. It’s really hard to heal when you don’t have an answer.

My mantra was, “What if I we would have just kept her at home? What if I’d been more vigilant about saying she sleeps on her back, not just assume that everybody knew that you place a baby on their back for sleep. Would she still be alive today?”

I can still play that track if I allow myself, but I have to say, 13 years later, I am where I am. She is where she is. So what can I do that’s positive and forward moving? That’s what she’d want for me.

No child, I think wants their parent to suffer and suffer and suffer. They want them to be the resilient, loving, caring person that they were, so that’s what I have in my mind – keeping the positive impact and knowing that maybe my daughter can have that positive impact through me to help other families.

Aileen Carrell is board president of Northwest Infant Survival & SIDS Alliance, one of the oldest SIDS nonprofits in the country.

This interview has been edited and condensed.