Why more black students attend charter schools in WA

The state’s eight charter schools are not technically charters right now. The state Supreme Court invalidated the original charter law last year.

Since then, the schools have either operated independently or as part of a district near Spokane – even if they’re located across the state.

Thanks to a new law, the schools will be charters again this fall and can still call themselves charters in the meantime.

These publicly-funded, privately-run schools were promised to Washington voters as a way to serve at-risk students who struggle in traditional public schools.

TRANSCRIPT

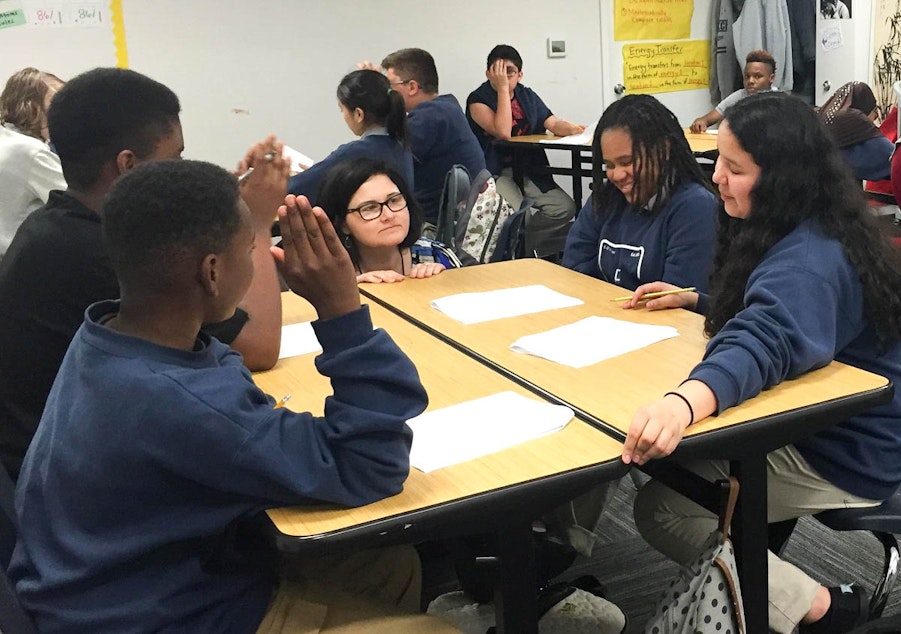

Walking through the halls of Excel Public Charter School, you’ll see that most of the students are children of color.

Founder Adel Sefrioui says that’s no accident. When he scouted sites for the school, he looked for a location in the south end of Kent – a diverse part of town and home to many low-income families.

Adel Sefrioui: “We really wanted to serve a population of students that was representative of the Kent community. We set out from the very get-go to serve students who were historically underserved.”

Excel has a lot more black students than the surrounding school district. That’s true for most of the state’s charter schools. According to enrollment data the schools gave KUOW, some average two or three times as many black students compared to the districts in which they’re based.

That’s significant because black students tend to lag behind white and Asian students academically.

Sefrioui attributes much of the black enrollment at his school to the fact that the charter is based at a largely African-American church.

Adel Sefrioui: “Although we are not affiliated with the church as a public school, I think the members of the congregation saw a lot of value in signing their kid up in a public school that happens to be in their building.”

Poor students also tend to struggle in school, so the state’s charters promised to target kids from low-income families. For the most part, they also met that goal.

Bob Bifulco: “That general pattern seems consistent with what’s seen in a lot of other places – often low-income and students of color compared to the districts they’re serving in.”

Bifulco is a professor of public administration at Syracuse University. He’s studied the demographics of charter schools in other states. Bifulco says there are a lot of ways that charters end up with a particular student population.

The schools often appeal to families who don’t feel the nearby public schools serve them well. Charters might also do as Excel did: Locate in a neighborhood that’s home to their target demographic and market to those families.

But there are also areas in which Washington’s first charter schools appear to be falling short.

Two major groups of students who often struggle in traditional public schools are kids who need special education services and English Language-Learners students. State law lists kids who need ELL and special ed services as particular focus areas for charters. Most of the state’s charter schools enrolled fewer special education and ELL students than the district average.

Bifulco says that’s a trend he’s seen nationwide.

Bob Bifulco: “Charter schools are often set up for a specific mission and serving certain high-needs special education students is just not part of their mission and they don’t have a lot to offer those students. Whereas public school districts have no choice but to take that on as part of their mission.”

When it comes to ELL students, Bifulco says lower enrollment might be due to the difficulty reaching out to immigrant families. Some charter leaders we spoke to said that was the case, or that immigrant families wanted their kids to go to school closer to home.

In some states, charter schools have been shown to have used selective admissions processes to screen out students they deem harder-to-teach. Or counseled families out if their students proved difficult or expensive for the school. That can help charters keep standardized test scores up and keep them in business.

There’s no evidence that’s happening in Washington. But Bifulco says because school demographics can vary so dramatically, there’s no easy way to compare the success rate of a charter school to a traditional public school.

Such comparisons will be tempting for analysts when state test scores are released this summer.